Data collection can be one of the toughest, yet most rewarding and exciting parts of the PhD journey. But no one could prepare me for the tiresome and emotional rollercoaster I was about to step onto with my first termite experiment. My past research experiences were with ants and bees, both fairly manageable animal colonies to keep and study in a lab environment. Despite being forewarned about the difficulties of working with termites, upon picking a study system, I couldn’t ignore my natural curiosity for these cryptic subterranean animals. I became especially interested in termite social behaviors when faced with infected members of the colony.

Subterranean (or “under the earth”) termites live in large colonies underground, where they tunnel through soil in search for their next wooden meal. Moist soil and wood habitats are also ideal environments for the termites’ biggest enemy: fungus. Fungi are the most common insect pathogens. For as long as pathogens and their hosts have existed, a coevolutionary arms race continues, where each is trying to one up the other by increasing its harmful effects (pathogen) or increasing its defenses (host). This type of arms race between fungi and termites has given rise to many effective antipathogenic behaviors in subterranean termites. The behaviors between infected and healthy colony members vary based on the level of infection (i.e., how long the fungal infection has been developing in the host). For the first twelve hours of the infection, the fungus stays on the surface of the termite. Since the fungus is only on the surface of the termite, its fellow colony members will help the infected termite by grooming the fungus off of the infected termite’s shell. However, after 12-hours, the fungus is able to penetrate the hard outer shell and internally infect the termite. Once the infection is inside of the termite, external grooming will no longer save the infected termite. Therefore, the healthy termites strategy becomes a bit more … aggressive, to say the least. About 15-hours after the original exposure of the termite to the fungus, healthy colony members will start to cannibalize the sometimes still living infected termite. The goal of this behavior is to stop the infection from spreading to other members of the colony. “For the greater good!” is what I like to think the termites are thinking while sacrificing their infected colony member. Although we know what behaviors are conducted at these levels of infection, it’s still unknown as to which termites are conducting these behaviors. Is there a specific group of termites responsible for handling infected colony members or can any member of the colony do these behaviors? Finding this out was the goal of my first experiment.

Photo Source: Nicole Keough

Reaching my goal involved a lot of planning and prep work to make sure all of my termite and fungal protocols were sound. These preparations helped me anticipate some of the issues that may arise during my experiment. Unfortunately, not everything can be tested in advance, which is why many researchers create backup plans. However, when faced with my first speed bump, I learned that as a scientist it’s always good to have backup plans for your backup plans. This first speed bump was due to many sad looking bait buckets. A year prior, some fellow grad students and I had placed 18 bait buckets with wood into the ground in order to lure termite colonies into them. The bait buckets hadn’t been touched since placed into the ground. To my dismay, only one bucket had termites in it; I needed way more than that for my experiment. What I did find were plenty of wood cockroaches! Hence the backup plan to my backup plan of just using fewer termites was to shift to studying wood cockroaches (i.e., the termites’ closest relatives!). Fortunately, I didn’t have to use this contingency plan as a few days later, my interns and I went out and found many more termites under a fallen tree near my buckets. I now had more than enough termites to run my experiment.

Photo Source: Nicole Keough

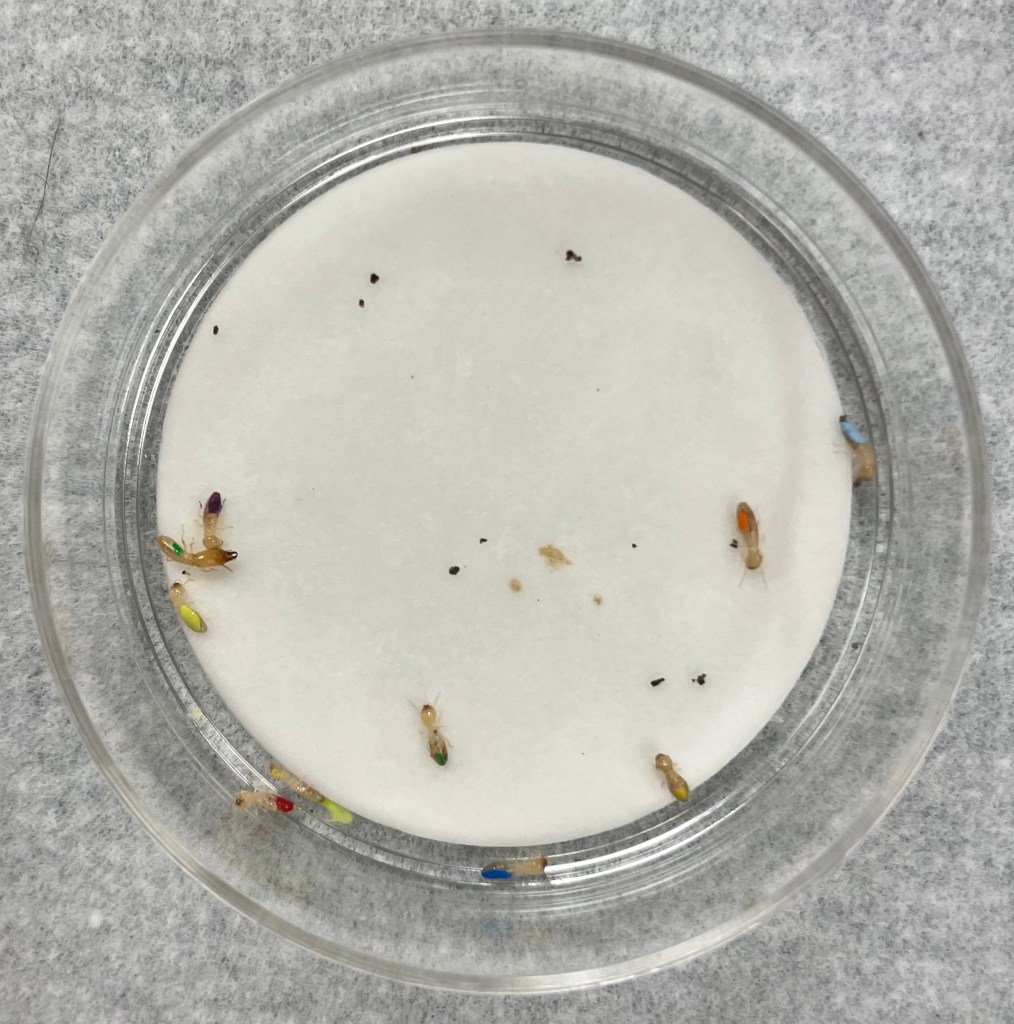

After this first hurdle, I figured everything else would be full steam ahead. Instead what happened was once one issue was settled, another popped up in its place. Once collected, many of the termites started dying in the lab. This was an anticipated issue of studying termites, as they’re underground environments have very different moisture and gas levels compared to the lab environment. However, I was still surprised by how high the death rates were. Once the termite death rate slowed down, I realized that we may not be able to measure all of the heads of each termite in time, despite having a team of undergraduate interns working every day to take these measurements. Why do we need the head widths of each termite? The relative head width of termites can be used as a proxy for age with smaller heads being younger termites. One major question of my experiment was to see if there is a correlation between age and antipathogenic behaviors. Thanks to the hard work of these undergraduate interns, we were able to measure enough living termites to include in the experiment, but this wasn’t the last speed bump I would experience in this experiment. Still to come was a problem that I had tested with much success, but once it came to the real deal, something still went sideways. After measuring the termites’ head widths, we grouped and marked them using topical paint based on their size. When testing the paint, it stayed on the termites, with some still alive and painted in the lab four months later. Despite the test termites handling the paint really well, a large percentage of the experimental termites had removed their paint after only a few days. I’m not exactly sure why this procedure didn’t work as well in the experiment. I have some ideas that perhaps a future side project will let me get to the bottom of. But alas, we move on! My interns and I repainted the termites, increasing our number of observable termites for the experiment and accounting for the fact that some may still remove it prior to the start of the experiment. Thankfully, this was the last major issue I had to navigate through for this experiment.

Photo Source: Nicole Keough

Despite all of the hiccups, I made it to the other side with some data! It may not have been exactly what I had hoped for, but I do have some behavioral data to quantify and analyze. Before I analyze this data, due to all of the speed bumps I encountered during the course of this project, I wanted to try a different, more technical way of approaching this research question. This new approach will be to observe termites’ antipathogenic behaviors through automated video tracking. Ideally, by using automated tracking, I would be able to measure head widths and quantify interactions between termites using video software rather than manually measuring, marking, and observing termites. I’m now in the process of figuring out how this works, so stay tuned!

To end this article, I wanted to leave you all with three lessons I learned from my first experiment:

- Having backup plans for your backup plans is always a good idea – even if it’s just to give you peace of mind.

- Take some time to appreciate the duality of an animals’ delicate, yet resilient nature.

- If at first you don’t succeed, try try again … but not in the exact same way!

Nicole W. Keough (formerly Korzeniecki) is a PhD candidate in the Animal Behavior Graduate Group at UC Davis. She studies the behavioral and genetic organization of social antipathogenic responses in Western subterranean termites. More broadly, Nicole is interested in the dynamics of eusociality and host-microbiome interactions.

[Edited by Cassidy Cooper]