As dusk consumes the Namib desert, shadows lurk into the crevices between 600 million year old rocks, records of a watery world just before the rise of animals. The silence is piercing but not unusual: these southern African mountains are too dry for insects, and too far from people, aside from the odd geologist. So when a stifled snort and the sensation of movement breaks the star-lit evening, it is surely a leopard. When that snort morphs into a higher-pitched, yipping guffaw, it is most definitely a pack of hyenas. But, the shadows bound into stripes, and crest the ridge: a harem of mountain zebras (Equus zebra) making their surprisingly high-pitched yet gruff alarm call.

Shorter and with bigger ears, the mountain zebra looks like a donkey-ified version of the more common plains zebra (Equus quagga). Like your fingerprint, mountain zebras each carry a unique stripe pattern [1]. Plains zebras have these too, but mountain zebras have stripes all the way down to their hooves, yet stripe-less bellies (in case you need to remember this: plains zebras get plainer closer to the plains). There are a number of possible reasons why zebras have stripes, from blending in to avoiding flies.

Another key distinguishing feature of the mountain zebra is the presence of a dewlap, or flap of skin on the neck, which plains zebras don’t have (again, so plain). Lots of other animals have dewlaps – like lizards and cows. They might help these animals cool off, which would make sense given the warmer, more intense environment of mountain zebras relative to the plains. Alternatively, dewlaps might be attractive in the eyes of female mountain zebras. As it turns out, dewlaps are more pronounced in male zebras, which, like male horses, are called stallions. Yet another possibility is that the dewlap suggests to predators that the individual sporting it is healthy enough to risk wearing an actual lion-mouth-hold and is therefore not even worth messing with. This strategy of males demonstrating their capacity to flirt with death could also tie-in to the female attraction hypothesis (think of humans driving their car too fast to impress a potential partner) [2].

Some of these hypotheses might relate to their social system. Plains zebras congregate in herds of up to 80 individuals. But mountain zebras live in small harems of no more than 15 individuals. They include one dominant stallion of at least five years old, one to five females, and their less than two-year-old offspring. That leaves most stallions to either wander alone or in bachelor groups. The composition of a harem can be stable for years, but stallions that are old or weak are usually displaced by other stallions from nearby bachelor pods [1]. Bet you can’t guess which large herbivorous primate their social system reminds me of!

A “sizing-up” process results in some stallions having harems while others only see females from afar. It probably plays out through the combination of stallions attracting newly-moved-out female foals to join them in new harems and a series of ritualized displays. During these “challenges,” rival males—whether they’re head of a harem or in a bachelor group—step off to the side. They assess one another through orderly, ritualized nose-touching, side-by-side pushing against one another, nose-to-genital contact, and sometimes mounting. Observations of facial wounds suggest that real aggressive fighting also occurs and can lead to harem takeovers. Sometimes harems and bachelor groups hang out near one another. Together, individuals forage for grass, bark, and leaves or drink at a waterhole in the montane desert landscape [1, 3].

While the stallion is the top zebra in the mountain zebra pecking order, the females (also called mares) also have a hierarchy. Unlike that primate I mentioned, once established in a group females rarely switch to another male’s group. This could suggest that the male-male “challenges” are more for the males to establish and maintain dominance and submission than for the females to get an idea of who might be the better protector for their offspring from roaming leopards, lions, and hyenas. It is likely that it’s the females in a harem who typically decide where the next move will be while foraging, as they take the lead ⅔ of the time and are the first to leave when sensing potential danger [1].

Last Creature Feature we read about an indicator species. The mountain zebra also serves an important role in its ecosystem, but in a different way. By actually shaping the distribution of the very vegetation they feed on, mountain zebras are “ecosystem engineers.” We have seen some other examples of ecosystem engineers in the past (squirrels and lyrebirds). Mountain zebras “engineer” specifically and (probably) inadvertently by dust bathing! They roll around in rolling pits they create, which get bigger as many individuals use them repeatedly over time. Scientists recently discovered that the soil in rolling pits is relatively finer and higher in nutrients than surrounding soil [4]. These areas thus hang onto moisture longer after rains and support denser communities of the very plants that zebras feed on [4, 5]!

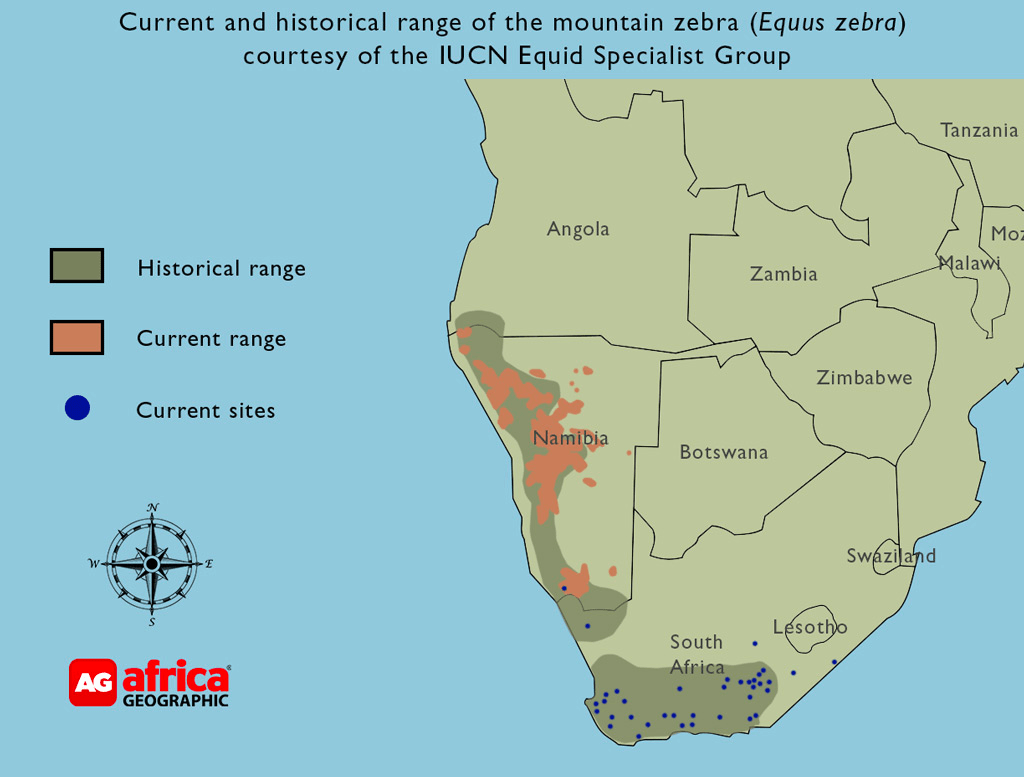

The mountain zebra population suffered extreme losses due to hunting in the last century but has since recovered to nearly 35,000 individuals today. The population is mostly in Namibia but also distributed patchily in reserves in South Africa. Mountain zebras remain vulnerable to extinction due to inbreeding, drought, limited available habitat, and overhunting [6].

At left, mountain zebra range, and at right, plains zebra range [Source]

Written by: Alice Michel is a third-year Animal Behavior PhD student. She currently studies how animal social groups share space and communicate with one another. When she’s not recording gorillas in the swamp, she enjoys biking, taking pictures of trees, and sunshine.

References

[1] Penzhorn, B. L. (1984). A Long-term Study of Social Organisation and Behaviour of Cape Mountain Zebras Equus zebra zebra. Zeitschrift Für Tierpsychologie, 64(2), 97–146. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0310.1984.tb00355.x

[2] Bro-Jørgensen, J. (2016). Evolution of the ungulate dewlap: Thermoregulation rather than sexual selection or predator deterrence? Frontiers in Zoology, 13(1), 33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12983-016-0165-x

[3] Joubert, E. (1972). The social organization and associated behaviour in the Hartmann zebra Equus zebra hartmannae part 1. Madoqua, 1972(6), 17–56. https://doi.org/10.10520/AJA10115498_10

[4] Wagner, T. C., Uiseb, K., & Fischer, C. (2021). Rolling pits of Hartmann’s mountain zebra (Zebra equus hartmannae) increase vegetation diversity and landscape heterogeneity in the Pre-Namib. Ecology and Evolution, 11(19), 13036–13051. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.7983

[5] Muntifering, J., Ditmer, M., Stapleton, S., Naidoo, R., & Harris, T. (2019). Hartmann’s mountain zebra resource selection and movement behavior within a large unprotected landscape in northwest Namibia. Endangered Species Research, 38, 159–170. https://doi.org/10.3354/esr00941

[6] Gosling, L.M., Muntifering, J., Kolberg, H., Uiseb, K. & King, S.R.B. (2019). Equus zebra (amended version of 2019 assessment). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: e.T7960A160755590. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-1.RLTS.T7960A160755590.en. Accessed on 08 July 2023.

[Edited by Jacob Johnson]