In the Field

“There aren’t any sharks out there” is something I commonly hear from people in Oregon and Washington. Truth is—there are definitely sharks out there. We just don’t know anything about them, or the role that they play in the Pacific Northwest’s ecologically, economically, and culturally important ecosystems. That’s what the research in the Big Fish Lab focuses on—what role do they play? Where do they go, and what do they eat when they’re there? In doing so, we’re trying to raise awareness that sharks are in the region and they play super important parts in healthy ecosystems!

Photo credit: Jess Schulte

As a PhD student, my research centers on an abundant apex predator in the coasts of Washington, Oregon, and California: the Broadnose Sevengill shark (Notorynchus cepedianus) [1, 2]. These sharks live worldwide in shallow coastal waters and, along the western US coast, can be found from southeastern Alaska to southern Baja. They reach up to 3 m (~10 ft) and over 180 kg (400 lbs), and, in other studies done around the world, have exhibited ontogenetic feeding, which simply means that they change their food preferences as they get older. In other words, they eat small animals (crabs, small fish, etc.) when they’re small, and eat larger animals (big fish, marine mammals, other sharks and rays, etc.) as they get larger. And it’s because of this that I wonder—what are they eating here along the Pacific Northwest coast? We have a lot of important fisheries in the region: multiple species of salmon, crab, halibut, sturgeon, to name a few. Are sevengills eating these species, and if so, how much are they impacting the populations themselves as well as the broader ecosystem?

Photo credit: Crea Andrews

In order to figure this out, I conduct long field days to catch sevengills and gather both short-term and long-term data on them. I’m looking at sevengill movement (a.k.a. where they go) along with their foraging ecology (a.k.a. what they eat) and combining those things together to understand their impact. Luckily, many adult sevengills in the Pacific Northwest spend their summer in a single location—Willapa Bay, WA—which makes it an ideal location to find them! My field work starts by prepping all of my sampling supplies along with our boat and specially-built (by me!) shark cradle. The cradle allows us to restrain and lift the sharks out of the water onto the boat with us. After inserting a hose into the shark’s mouth to provide aeration over the gills, we’re ready to work up the animal and get it back into the water.

Photo credit: Jess Schulte

Working up the animal is just the process of taking all our measurements and samples. Measurements include the animals’ length, weight, and whether it’s male or female. Samples include taking very small amounts of muscle and blood, which I can use to give information about sevengill long-term feeding habits over the previous 12 months. Think, “you are what you eat.” It’s the same for animals! Using a process called stable isotope analysis, I can get hints at what the sevengills ate within the last year. For short-term feeding habits, the process is a bit less technical. Using a common lavage technique, we can help the sharks regurgitate what they currently have in their stomachs. In other words, I hold a bucket under the mouth while the rest of my team lifts the shark, allowing gravity to bring its stomach contents forward and into my trusty bucket. This tells us what the sharks are eating right now, which is sometimes smelly but always exciting to look through (spoiler alert: sevengills eat a variety of prey!). Lastly, I tag some of them with acoustic tags, which help tell me where the sharks go after I release them.

By collecting this comprehensive data, I hope to help answer important questions about these abundant, apex predators, and maybe other shark species in the region as well! Hopefully, my research will help managers better understand our ecosystems and the diversity of species that live in it. Stay tuned with the @Big_Fish_Lab on social media to keep up with this exciting research!

Meanwhile, Back in the Lab…

While field work involving sharks is definitely super exciting and flashy, you can’t have the fun field work without also spending a lot of time in the lab! This is where I (and other Big Fish Lab members) come in. I’d argue that lab work can be just as exhilarating as field work! In our day-to-day lives, my lab members and I spend our time arms-deep in the stomachs of another species, the salmon shark (Lamna ditropis), playing “shark science detective” in order to determine what salmon sharks eat and how that might impact fish populations in the Pacific Northwest. It’s always an exciting moment to see a fully intact fish, or to find an otolith (a specialized structure found in the ears of fish) or squid beak hidden in the stomach lining. This stomach content analysis lab work is a key piece of the Pacific Northwest salmon shark puzzle that I and fellow Big Fish Lab members Reilly Boyt and Dr. Alexandra McInturf are working to solve [3].

Photo credit: Maddie English

While I can often be found deep in the salmon shark stomachs alongside my lab mates, my research actually involves taking the stomachs a step further. As a first year master’s student at Oregon State University, I study microplastic ingestion and trophic transfer (i.e., transfer from prey to predator) of microplastics in salmon sharks off the coast of Oregon.

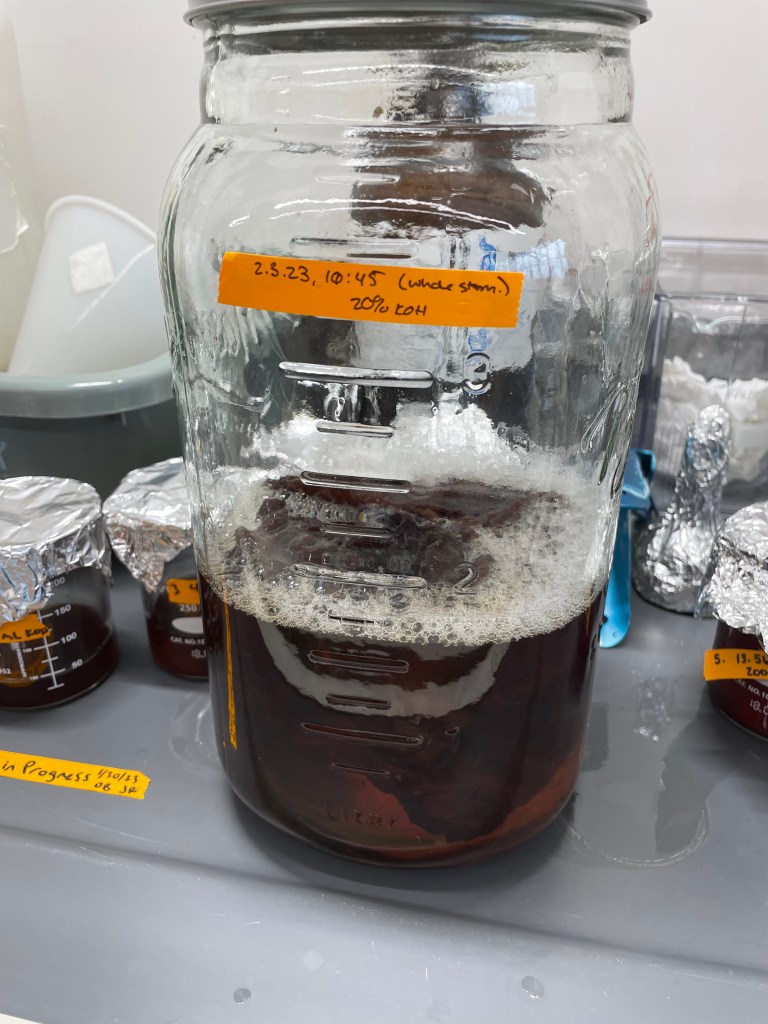

When the shark stomachs are done being processed for prey contents, I put them in a solution to dissolve them. I’ve been told the process looks a bit like I’m distilling my own home-brewed beer (or lab-brewed in this case), to which I respond, “If only that’s what this was!” I’m not sure it would smell any better, though.

Photo credit: Maddie English

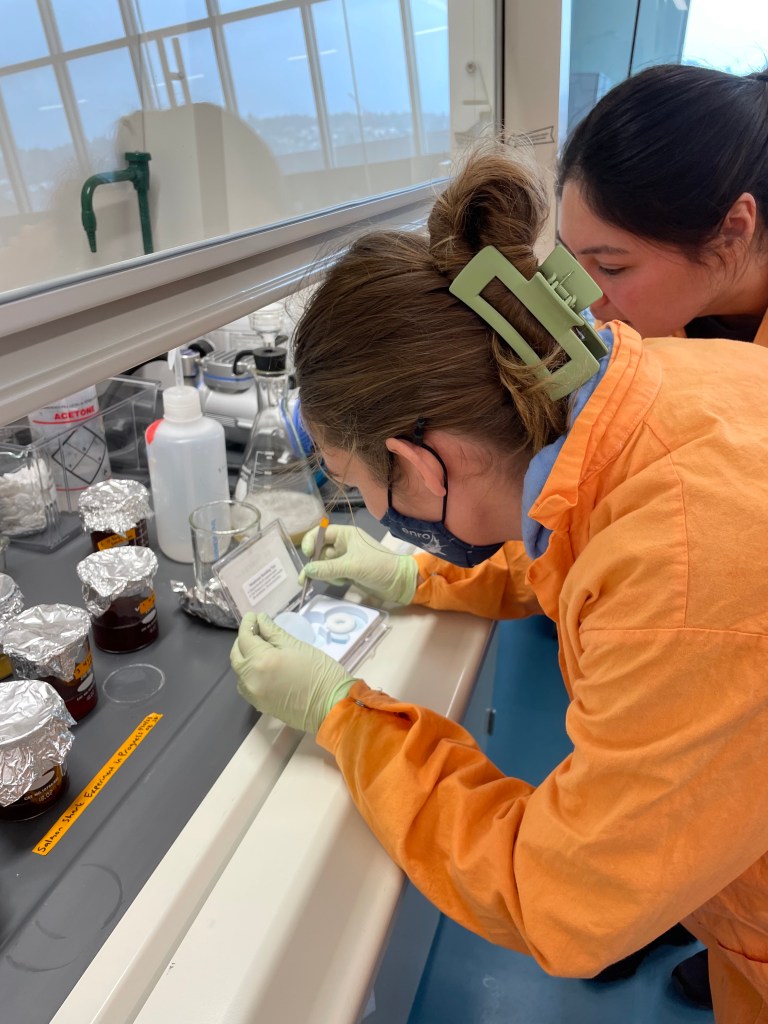

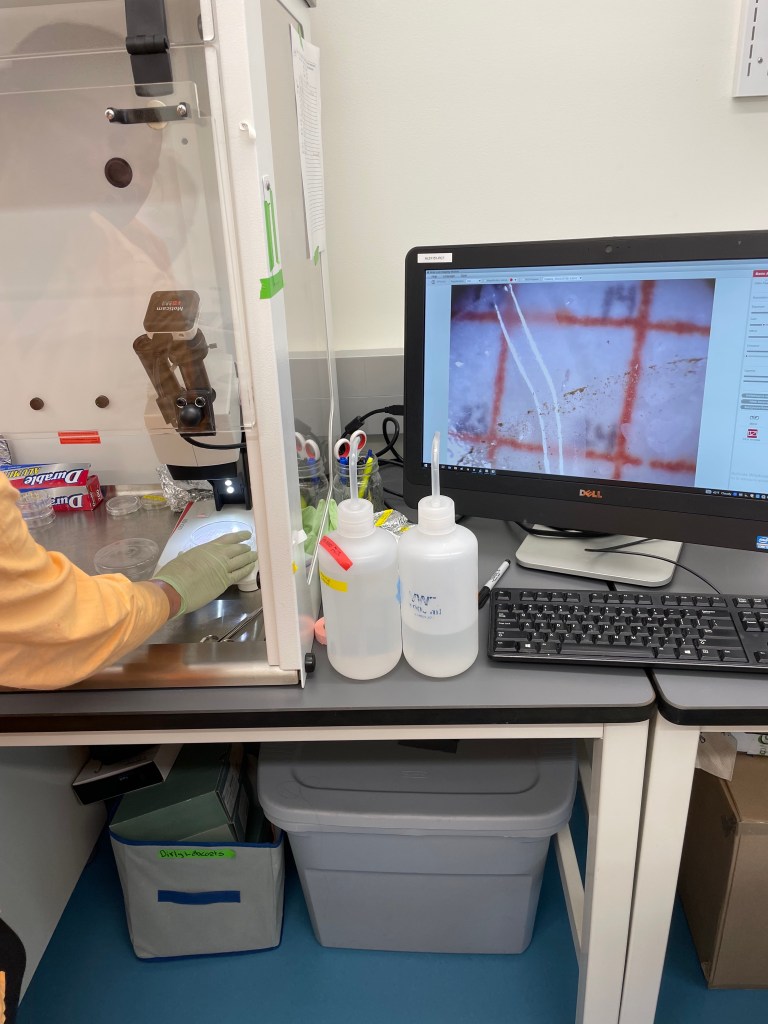

After the stomachs are fully dissolved, I embark on the tedious process of running the contents through a vacuum filter and picking through the filters under a microscope to look for microplastics. After picking through every filter, I’ll identify the types of plastics I’m finding using visual characteristics like size, color, and shape. My goal with this research is to understand how many microplastics salmon sharks are ingesting and where these microplastics are coming from (e.g. their prey).

Photo credit: Maddie English

There is still little known about the presence and role that sharks play in ecosystems in the Pacific Northwest and little known about how we, as humans, impact them. My hope is that through my and my teammates work, we will be able to shine a light on our local sharks and show people why they are so cool and so important to the continued survival of coastal marine ecosystems! If you want to follow along with the Big Fish Lab’s research you can check out our social media: @Big_Fish_Lab and our lab’s website here.

Jess Schulte and Maddie English are graduate students in students in the Shark and Fish Movement and Behavioral Ecology in Oregon State University’s Big Fish Lab working under Dr. Taylor Chapple

Jess Schulte is a 3rd year PhD student and wrote the field-focused portion of this piece. Her research interests began at the US Geological Survey, examining the impact of invasive species in Florida ecosystems. She then went on to work in Coastal Resource Management as a Peace Corps Volunteer in the Philippines before conducting climate change work at the State Department in Washington D.C. Jess studies the movement and foraging ecology of broadnose sevengill sharks in Washington and Oregon, and hopes to illuminate the top-down ecological role of these apex predators.

Maddie English is a 1st year Master’s student who wrote the lab-focused portion of this piece. Maddie studies mechanisms of salmon shark microplastic ingestion in Oregon.

References

[1] Ebert D (1989) Life history of the sevengill shark, Notorynchus cepedianus Peron, in two northern California bays. California Fish and Game 75:102–112

[2] Ebert DA (2003) Sharks, rays and chimaeras of California. University of California Press, Berkeley, 297 pp

[3] Savoca, M. S., McInturf, A. G., & Hazen, E. L. (2021) Plastic ingestion by marine fish is widespread and increasing. Global change biology, 27(10), 2188-2199.

[Edited by Cassidy Cooper]