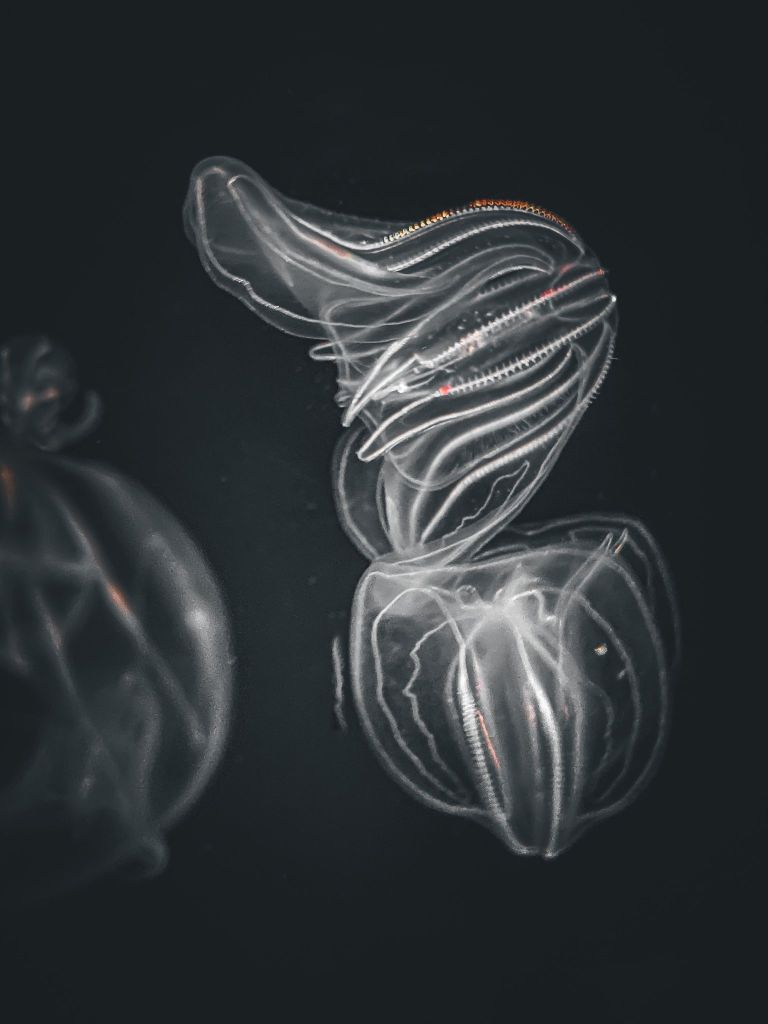

Imagine yourself submerged in a tropical sea: a secret world hidden from the surface, yet brimming with life. Amidst the vibrant explosion of colors and turquoise waters, something shimmers into view—the comb jellyfish (Mnemiopsis leidyi). The mesmerizing creatures known for their bioluminescent abilities glide gracefully with the currents. Join us on an enchanting journey as we unravel the mysteries of these watery denizens.

Before diving into the comb jellyfish’s world, it’s essential to understand that they are not actually jellyfish! Although they look superficially similar, as floating gelatinous creatures that have existed for over 500 million years, they are not in fact closely related. Comb jellyfish belong to the biological group, or “phylum,” called Ctenophora, while jellyfish belong to the phylum Cnidaria. This grouping distinction reveals that, despite their many apparent similarities, their anatomy and evolutionary histories are dramatically different. For example, jellyfish use stinging tentacles in order to catch and eat food. Meanwhile, comb jellies lack stingers. Instead, they use sticky cells on their tentacles or current generated by their cilia to pull prey such as plankton into their mouths [1].

As we explore the warm waters, coral reefs crowded with fish surround us, forming a secret city perhaps more magnificent than the legendary lost city of Atlantis. To our right, comb jellyfish illuminate the coral-lined avenues with a mesmerizing display of colors—ever-shifting patterns of reds, oranges, and greens! These incredible creatures possess the ability to generate light through specific genes that produce photoproteins. With a repertoire of ten different photoproteins, comb jellyfish emit a stunning array of colors, resembling a radiant rainbow [2]. This allows them to lure prey while also serving as a strategic method of camouflage by mimicking the light of the sun [1]. This helps them escape predators like fish, sea turtles, crustaceans, and even other comb jellies [3]!

Imagine being 95% water—a composition more liquid than a watermelon [4]. This watery physiology and their small size (about the size of a golf ball) makes comb jellyfish remarkably adaptable and able to live in all parts of the ocean. While they have some degree of control over their small-scale movements via their lateral, gelatinous “combs” [1], they often have no choice but to drift through the ocean’s overpowering currents.

Unlike humans with a centralized brain, comb jellyfish possess a nerve net—a network of interconnected nerve cells distributed throughout their bodies [1, 5]. The nerve net processes sensory information and allows them to coordinate responses, much like our five senses (touch, sight, hearing, smell, and taste). Notably, comb jellyfish have additional sensory structures called statocysts, which aid in maintaining balance and orientation by sensing Earth’s gravitational pull [1]. This remarkable adaptation grants them a keen sense of position within the water, even when being thrown around in a turbulent current. This is especially important considering that they don’t even have eyes! Nevertheless, the same exact regions that emit light through photoproteins actually also express light-detecting proteins [2]! This means that, despite not having eyes, they can still sense light. That opens the door for an additional function of their bioluminescence: communication with other comb jellies [6].

In the depths of their secret city, the comb jellyfish reigns, dazzling with its bioluminescence and graceful movements. But they hold promise for us up at the surface too: further research into their photoproteins and the genetic mechanisms behind comb jellyfish bioluminescence holds the potential for advancements in biotechnology, including new imaging techniques, biosensors, and bio-inspired lighting technologies. Moreover, understanding their role and impact in marine ecosystems is crucial for managing and conserving oceanic resources. Future research on comb jellyfish life history could inform strategies for fisheries management, ocean conservation, and mitigation of jellyfish population explosions (or “blooms”), which seem to be increasing with climate change and may cause negative effects on ecosystems [1]. By exploring the intricate adaptations of the comb jellyfish, such as their unique way to sense the world through their nerve net and their bioluminescence, we can gain a deeper appreciation for these enigmatic creatures and of the sensory diversity of all life on Earth. Let us continue to uncover the oceans’ secrets and unlock the door to new discoveries that lie beneath the turquoise waters.

Written by: Chris Kwon is an Education Volunteer at the Aquarium of the Pacific in Long Beach, California. Chris’s involvement with marine animals and his efforts to inspire the public to engage with them have ignited a passion for animal science that he plans to pursue in college and beyond, with the ultimate goal of contributing to the welfare of all animals. Whether it’s caring for dogs, cats, or tiny mammals, Chris finds excitement in supporting and nurturing other creatures.

References:

[1] Collins, A. & The Smithsonian Ocean Portal Team. (2018, April). Jellyfish and Comb Jellies. Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. ocean.si.edu/ocean-life/invertebrates/jellyfish-and-comb-jellies.

[2] Schnitzler, C. E., Pang, K., Powers, M. L., Reitzel, A. M., Ryan, J. F., Simmons, D., … & Baxevanis, A. D. (2012). Genomic organization, evolution, and expression of photoprotein and opsin genes in Mnemiopsis leidyi: a new view of ctenophore photocytes. BMC biology, 10, 1-26.

[3] National Marine Sanctuary Foundation. (2021, April 6). Sea Wonder: The Comb Jelly. marinesanctuary.org/blog/sea-wonder-comb-jelly/.

[4] Viking Eco-Tours. (2022, August 25). Comb Jellies. www.vikingecotours.com/bioluminescent-comb-jellies/.

[5] Buehler, J. (2023, April 20). Comb jellies have a bizarre nervous system unlike any other animal. ScienceNews. www.sciencenews.org/article/jellyfish-nervous-system-animal

[6] Morin, J. G. (1983). Coastal bioluminescence: patterns and functions. Bulletin of Marine Science, 33(4), 787-817.

[Edited by Alice Michel & Jacob Johnson]