It’s late spring, and the weather in Puerto Rico is perfect for going swimming at the beach. As you meander through the leaf-litter-strewn forest that prefaces the beach, you encounter a small bird plopped on the ground. It looks disoriented – it must be a chick that fell from the trees, you think, so you reach out to help it, but stop! This isn’t a chick at all; you just encountered a type of nightjar, the relatively unknown ground-nesting Querequequé (Antillean Nighthawk, Chordeiles gundlachii).

Borinkén (the pre-colonial name of Puerto Rico) is home to three species of nightjars; one of them, the Guabairo, is a year-long resident [1]. The other two, meanwhile, are seasonal arrivals (Caprimulgus carolinensis and the Querequequé). It’s during the Querequequé’s mating season (May to July) that you usually see a rise in sightings of nightjars in Puerto Rico [1].

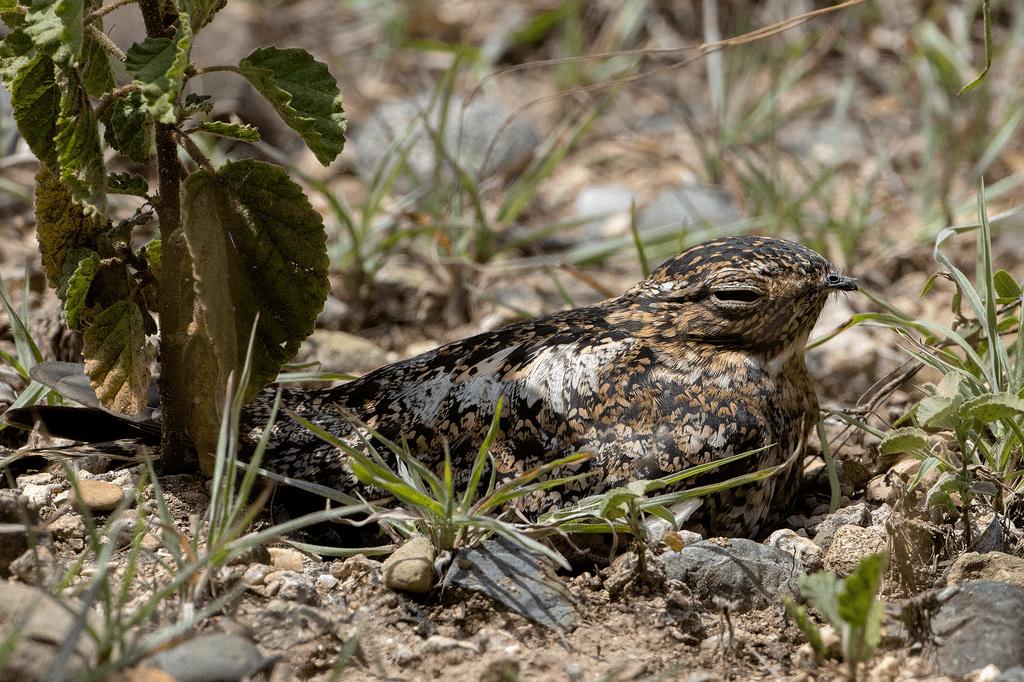

Querequequés congregate in coastal areas, where their speckled, sandy-colored plumage is especially well equipped to camouflage them. However, they have also been spotted in agricultural areas, urbanized towns, and even deep in the forest [2]. As long as there are insects to eat and leaves to hide in, the Querequequé doesn’t appear to be super picky about its home.

Camouflaging in the leaf litter is critical for these birds because they lay their eggs on the ground, so they need to blend in with their surroundings to properly protect their progeny. Earlier I called the Querequequé a ground-nesting bird. However, the phrase “ground-nesting” is a bit misleading because the bird doesn’t really do any sort of collecting or construction of the nest. The female Querequequé simply finds a comfy pile of leaves and lays one or two eggs there [3].

The female bird (left) with darker colors is larger than the male (right) with white chest markings. Which one do you think blends in the best with the ground?

Both male and female Querequequé contribute to raising offspring. As the main brooder, the female sits on the eggs most of the time while the male perches in a nearby tree. But if a predator approaches the nest, the female flies off, creating a distraction to draw the predator away from the eggs. If the predator is not tempted and still persists in trying to get itself an egg snack, the male dive-bombs the predator from his overhead perch [3]. As mentioned earlier, the Querequequé is very under-studied, so no one really knows who their predators are, but it seems likely that native raptors like owls and snakes like boas and introduced species like cats, dogs, and west Indian mongooses would enjoy hunting for them or their eggs [4].

Like many animals that call Borinkén home, the Querequequé has an onomatopoeic name. In other words, it’s named after the sounds it makes (listen below). Although its call is its distinguishing feature, we don’t actually know what the Que-re-que-que sound is meant to communicate!

All nightjars are crepuscular. This means that they prefer to be awake and active at sunrise and sunset [1]. Because of this, it’s not uncommon for very well-meaning people to find these birds on the ground in the middle of the day and try to rescue what they see as a hurt bird. After all, what kind of bird just lays there on the ground? Their suspicions of this being a hurt bird solidify even more when they find they can just grab this sleeping bird with ease. As it turns out, the Querequequé does not exhibit much of a fear response when grabbed by a person outside of their active hours. The reason for this is a mystery. It’s possible that the guild of native predators they evolved with like owls and boas only hunted them at sunrise and sunset, but we can’t say for sure.

Incidents of well-meaning people disturbing nightjars are very common during nesting season. This is true for all of the nightjars in Puerto Rico, but especially so for the Querequequé because it’s the most abundant species of nightjar found in the archipelago. The problem is so prevalent that every year conservation organizations dedicated to Puerto Rican biodiversity put out educational campaigns advising people not to touch the birds [5].

Sadly, not many people research these birds [6]. Most of what we know about Querequequé comes from incidental findings in unrelated projects [2]. or by comparison to similar species [3]. Unless the animal directly benefits an industry, It’s not uncommon that native fauna goes understudied. So if you are a Puerto Rican naturalist, there’s still plenty of knowledge about our little friends waiting to be rediscovered. Why not give this teeny, onomatopoeic bird a chance?

Written by: Boricua born and raised, Sofía Meléndez Cartagena is a PhD student at UC Davis who specializes in running after bees and observing their beehaviours. Currently, she’s especially obsessed with observing the origins of social organizations in insects. When not obsessing over bees and their secrets, Sofía occupies her mind with contemplating how she can use her connection to the natural world to leave the world a better place.

References:

[1] Raffaele, H. A., Wiley, J. W., Garrido, O. H., Keith, A. R., & Raffaele, J. I. (1998). A guide to the birds of the West Indies. New Jersey, USA: Princeton University Press. https://bvearmb.do/handle/123456789/2496

[2] Delannoy, C. A. (2005). First nesting records of the Puerto Rican Nightjar and Antillean Nighthawk in a montane forest of western Puerto Rico. Journal of field ornithology, 76(3), 271-273.

[3] Gramza, A. F. (1967). Responses of brooding nighthawks to a disturbance stimulus. The Auk, 72-86.

[4] Vilella, F. J., & Zwank, P. J. (1993). Ecology of the small Indian mongoose in a coastal dry forest of Puerto Rico where sympatric with the Puerto Rican nightjar. Caribbean Journal of Science, 29(1-2), 24-29.

[5] Guabairo y Querequequé. Scribd. https://www.scribd.com/document/246020909/Guabairo-y-Querequeque

[6] BirdLife International. 2020. Chordeiles gundlachii. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T22689717A168858532. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T22689717A168858532.en. Accessed on 16 October 2023.

[Edited by Alice Michel and Jacob Johnson]