As you trek through the dark, damp foliage of the Indonesian nighttime, something is watching you. You can’t hear it over the whir and hum of nocturnal insects, but it can certainly hear you. It moves silently through the tree branches above you, hunting. Unbeknownst to you, its keen eyes lock onto its prey – dinner. With unnerving speed and accuracy, it pounces, landing on a thin vertical tree trunk just a few meters from you. Startled by the sound, you redirect the weak beam of your flashlight, and you finally get a good look at the predator and its unfortunate prey. The first thing you notice are the eyes – two bulging, eerie globes set in a minute face. Above the eyes are two leathery, ridged ears that are in constant motion, pivoting and twitching to attend to every strange sound the forest produces. A tail twice as long as the animal’s fist-sized body nearly brushes the forest floor. Thin, bony fingers grasp an unlucky katydid, which is quickly dispatched with several bites from needle-like teeth. You breathe a sigh of relief that you’re much too large to be on the menu for this carnivore. What you’ve just witnessed is a successful hunt by one of the world’s most unique primates – Gursky’s spectral tarsier (Tarsius spectrumgurskyae).

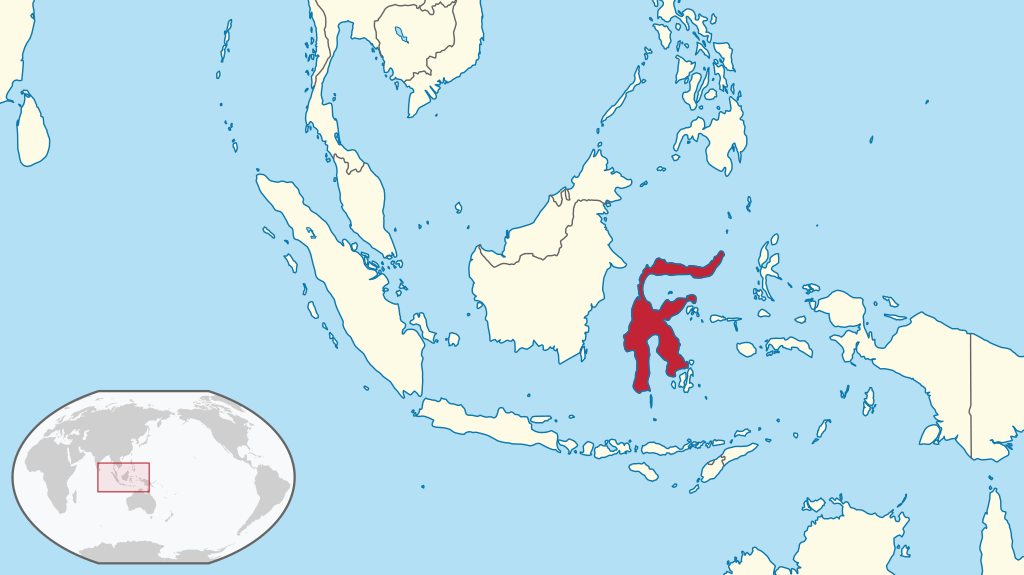

Found only on the tip of the northeastern arm of the Indonesian island of Sulawesi, Gursky’s spectral tarsier (Tarsius spectrumgurskyae) is just one of over a dozen species of tarsier scattered across Southeast Asia [1]. These small, rather peculiar-looking primates have the largest eye to body size ratio of all mammals. Each eye is larger than a tarsier’s own brain, resulting in a Yoda-like appearance [2]. Notably, however, their eyes lack a tapetum lucidum – the reflective structure that helps animals see in the dark and gives your cat’s eyes their eerie glow – making them difficult to locate by flashlight. Tarsiers make up for this with their enormous eyes and specialized brains, which allow them to see with very little light [3]. Wiry fingers and toes help tarsiers grip onto tree trunks and branches, and their long ankle bones (also called tarsi – the inspiration for their name) enable them to leap long distances from tree to tree [3].

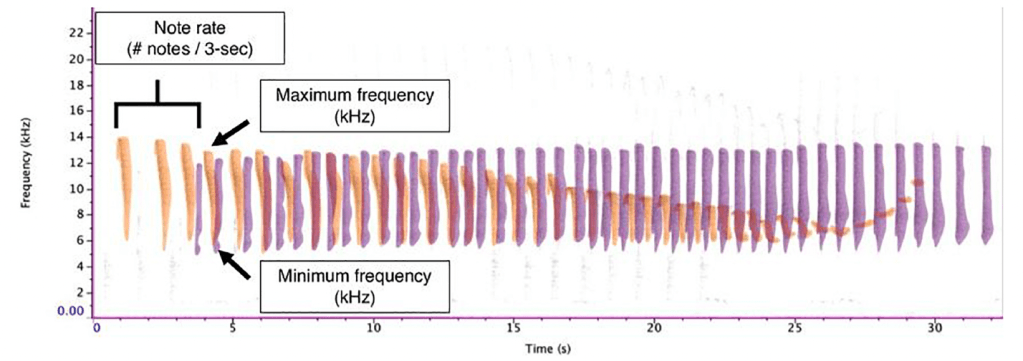

Most primate diets focus on plants, including fruits and leaves, with some protein coming from insects or other animals. Tarsiers, on the other hand, stand out as the only faunivorous primate species, with a diet consisting almost entirely of insects [3]. These voracious bug-eaters are devoted monogamists. Adults form mated pairs – one male and one female – and live in dedicated sleeping trees with their juvenile offspring. As the sun dawns after a long night of hunting, all individuals in a family group return to their sleeping trees and begin a fascinating ritual: the adult male and adult female begin to duet. To us, the squeaky duet sounds almost like the chirping of birds, but to the tarsiers, it is so much more. The male repeats a staccato of short, broadband notes, and the female sings a series of notes that begin high-pitched, dip down to a lower pitch and smaller bandwidth, and rise back up into a high-pitched finale. Juvenile offspring still living with their parents may occasionally join in, turning the duet into a chorus. Why tarsiers engage in this duetting behavior is still a mystery to researchers. Marking territory, advertising pairbond status to deter competitors, and pairbond formation and strengthening are three popular theories, but more studies are needed to determine the true purpose of tarsier duetting [4, 5].

Tarsiers are threatened on multiple fronts. Because of their small size and unique appearance, they are targets of illegal wildlife trafficking and the pet trade. Unfortunately, they do very poorly in captive conditions and often die shortly after confinement. In the wild, deforestation, including illegal logging, is particularly detrimental to tarsier populations. Since tarsiers are so heavily reliant on trees, removing forest cover directly removes their habitat. While Gursky’s spectral tarsiers are mainly found in Tangkoko National Park – a protected area – deforestation immediately outside the park and illegal logging inside the park are serious threats [1].

With their massive eyes, bizarre song, and unique diets, tarsiers are incredible examples of the biodiversity found in the order Primates. On your next chance encounter with one of these creepy-crawlies (or, in this case, creepy-leapies) of the animal kingdom, remember: you have nothing to be afraid of! Unless you’re an insect. Then, be afraid. Be very afraid.

Written by: Izzy Kier is a 1st year Ph.D. student in the Animal Behavior Graduate Group. She studies titi monkey pair bonding and how it relates to parenting and infant outcomes. She is interested in conservation work, both in the wild and in captive settings. In her free time, she enjoys hiking, camping, and reading. Originally from the East Coast, she loves exploring all that California has to offer.

References:

[1] IUCN. 2022. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2022-2. https://www.iucnredlist.org. Accessed on 6 October 2023.

[2] Collins, C.E., Hendrickson, A. and Kaas, J.H. (2005), Overview of the visual system of tarsius. Anat. Rec., 287A: 1013-1025. https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.a.20263

[3] MacKinnon, J., and MacKinnon, K. (1980). The behavior of wild spectral tarsiers. Int. J. Primatol. 1, 361–379. doi: 10.1007/BF02692280

[4] Clink, D. J., Tasirin, J. S., and Klinck, H. (2020). Vocal individuality and rhythm in male and female duet contributions of a nonhuman primate. Curr. Zool. 66, 173–186.

[5] Geissmann, T. (1999). Duet songs of the siamang, Hylobates syndactylus: II. Testing the pair-bonding hypothesis during a partner exchange. Behaviour 136, 1005–1039. doi: 10.1163/156853999501694

[Edited by Jacob Johnson and Alice Michel]