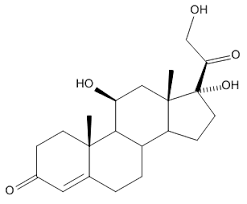

It’s hard to find a professional way to tell people that I’m a monkey trainer. On paper, I’m a graduate student, but I spent most of the summer and fall of 2024 training monkeys to chew on swabs so I could collect their spit and test it for cortisol, a hormone that can indicate stress [1]. I’ll spoil it for you right now – it was harder than it sounds.

Let me introduce you to the monkeys. I worked with ten coppery titi monkeys (Plecturocebus cupreus), a species of brownish-red cat-sized primates native to the forests of Peru. Adults form long-term pair bonds with each other, analogous to human romantic relationships [2]. My ten participants are housed at the California National Primate Research Center in Davis, California. Titis are notoriously neophobic – meaning they are extremely hesitant to approach and warm up to new objects, locations, and people – which can serve them well in the wild by keeping them safe from dangerous new things [3]. When in captivity, their neophobia can make training them very difficult, although not impossible. There are several approaches one can take when training animals, but positive reinforcement training is one of the most tried-and-true and ethical methods available.

The term “positive reinforcement training” sounds a bit academic, but if you’ve ever had a dog, you’re probably more familiar with it than you think. The basic premise is that when the animal does something you want them to do, you reward it. When the animal does something you don’t want them to do, you ignore it. As the animal progresses in training, you then only reward behaviors that are closer to the final action you want the animal to perform. If an animal doesn’t want to participate, you don’t force them to. For example, let’s say you want to train your dog to shake. You would start by rewarding your dog (with a treat or a pat or saying “good”) just for sitting, then for raising one paw a few inches off the ground, then finally for placing their paw in your hand. Once they know that “shake” means they need to place their paw in your hand, you would only reward them for doing that behavior, not for just sitting or lifting a paw off the ground. While there are certainly many differences between titi monkeys and dogs, I used the same basic procedure to teach the monkeys to chew on a swab and provide me with a saliva sample.

Because of their fear of new things, I didn’t start right away by shoving a long white swab in their face and expecting them to chew on it. I began by training each pair of monkeys to approach a designated target: a white plastic circle or rectangle clipped to one side of the door to their enclosure. Once they were comfortable approaching the target in exchange for a small piece of peanut, I began only rewarding them when they placed their hands on the target. After about a month of target training, I introduced the swabs – six-inch tubes of plastic-coated cloth-like material. At first, I rewarded any interaction with the swabs – approaching, grabbing with hands, sniffing, even accidental touching. My ultimate goal was to have the monkeys chew on the swabs without touching them with their hands (to avoid contaminating the swabs), so over time, I only rewarded the monkeys when they put the swab in their mouths or chewed on it without touching it with their hands. Training happened four times a week for about ten minutes per session per monkey.

After four months, I expected to have a few dozen saliva samples from each of my ten monkeys. In reality, I ended up with only 42 viable samples from only two of my monkeys after four months of work. My methods were sound and the approach was simple. So what happened? I was foiled by one of the most interesting topics in animal behavior: consistent individual differences, more commonly known as personalities. Essentially, each titi is different. My star student was Nymeria, a young female who couldn’t get enough of training. She would chew on the swabs until they were soggy and nearly falling apart. Whenever a session ended and I would move to take the target away, she would hold onto it. Unsurprisingly, most of my 42 viable samples are from her. If any of my ten subjects deserved a grade of F-, it’s Abe. An older male, Abe never once bit the swab. Most of our sessions consisted of him staring at me and rubbing his chest for ten minutes. Even in his most successful sessions in which he grabbed the swab a few times and I rewarded him with a piece of a peanut, he would take the peanut, peer at it, and drop it on the floor. The rest of the subjects fell somewhere between the Nymeria-Abe scale of enthusiasm for training. These individual differences could be attributed to a number of potential causes. A few of the monkeys (including Nymeria) had previous experience with target training. Some were quite a bit older than others. Some monkeys may simply not like peanuts as much as others do. With a sample size as small as ten, I can’t explore the reasons behind their individual differences, but it is certainly an interesting idea for future work.

With eleven of my 42 usable samples, I’ve run a preliminary proof-of-concept assay to determine if we can detect cortisol in titi saliva – and we can! My next steps include some more sample collection and more assays to see if salivary cortisol in titis changes over the course of the day and during/after mild stress. I anticipate that my lab (and other institutions with captive titis, like zoos) can use this method to monitor cortisol – an indicator of stress – in our colony and use it as an additional measure in further studies. I’ll leave you with a tip for when you next find yourself trying to collect monkey spit – be patient and know your monkey.

Izzy Kier is a 2nd year PhD student in the Animal Behavior Graduate Group. She studies titi monkey pair bonding and social preferences. She is interested in conservation work, both in the wild and in captive settings. In her free time, she enjoys hiking, woodworking, and reading. Originally from the East Coast, she loves exploring all that California has to offer.

[Edited by Cassidy Cooper]

References:

- Katsu, Y., & Baker, M. E. (2021). Subchapter 123D – Cortisol. In H. Ando, K. Ukena, & S. Nagata (Eds.), Handbook of Hormones (Second Edition) (pp. 947–949). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-820649-2.00261-8

- Dolotovskaya, S., Walker, S., & Heymann, E. W. (2020). What makes a pair bond in a Neotropical primate: Female and male contributions. Royal Society Open Science, 7(1), 191489. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.191489

- Titi monkey neophobia and visual abilities allow for fast responses to novel stimuli | Scientific Reports. (n.d.). Retrieved January 1, 2025, from https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-82116-4