Every May, we celebrate the moms out there with flowers, brunch, and heartfelt cards, but what about the moms out in the wild? The ones raising pups in burrows, ferrying tadpoles on their backs, or literally giving their lives for their young? Turns out, the animal kingdom is full of wildly good moms, each with their own unique parenting style. And as scientists have discovered, the biology of motherhood is as diverse as it is awe-inspiring. So this Mother’s Day, let’s look beyond the Hallmark aisle and into the forests, oceans, and burrows to celebrate the science of messy and magical motherhood.

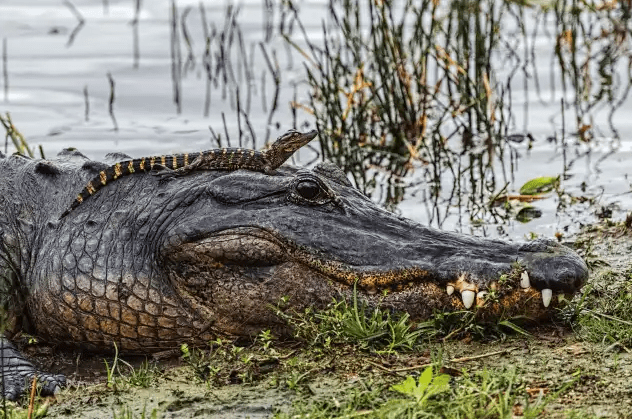

When it comes to animal behavior, no two species do parenting quite the same. Some go all in, some scamper away immediately after laying their eggs, and others find a sweet spot somewhere in between. In biology, these variations fall under the umbrella of maternal investment, a term that describes the energy, time, and risk a mother devotes to the growth and survival of her offspring [1]. Take the giant Pacific octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini), one of the most dramatic examples of maternal sacrifice in the animal kingdom. After a female octopus lays tens of thousands of eggs in a protected den, she enters a period of total devotion. She stops hunting. She stops eating. For months, she guards the eggs from predators and gently blows water over them to keep them oxygenated, rarely leaving her post. By the time the eggs hatch, she’s so depleted that she dies, her body literally breaking down from self-imposed starvation and a cascade of molecular processes that turn off her survival instincts [2]. It’s tragic, it’s awe-inspiring, and it’s a potent reminder that in the ocean, a mother’s love can be all-consuming – literally. Many may be surprised to learn that the American alligator is also an exemplary mother and provides parental care for her young, both before and after they hatch. American alligator females build nests which they guard and maintain until their eggs hatch in the late summer. Then, these awesome moms continue to protect their young from all manner of threats within their home range as they grow up [3]. On the opposite end of the spectrum are the various species of sea turtles, who take the “I believe in you, sweetie” approach to parenting. After hauling themselves ashore under cover of night, female turtles dig a nest, lay their eggs, cover them with sand, and return to the ocean – no bedtime stories, no checking for monsters, no goodbye kiss. And yet, this minimalist method works. Thousands of tiny hatchlings emerge weeks later and scramble toward the moonlit surf, with only instinct (and a lot of luck) guiding their way [3]. Then we have the elephants, whose approach to motherhood would make any daycare teacher proud. These social giants invest heavily in each calf, with pregnancies that last nearly two years and calves that remain dependent for years after birth. But mom isn’t alone in this venture – elephant families are famously cooperative. Non-maternal females, often older sisters or aunts, step in as caregivers, protectors, and even playmates in a practice called allomothering [4]. This shared care helps calves learn social behaviors and navigate their complex environments, while also giving mom a break. And for something a little more splashy, look no further than the poison dart frog. These vibrant amphibians live in the rainforests of Central and South America, where real estate for young tadpoles (specifically, small water-filled bromeliad) is in short supply. After transporting her tadpoles one by one to separate pools, the frog mom doesn’t just wave goodbye. She returns every few days to deposit unfertilized eggs into each pool, providing the only food source her developing young will have [5]. It’s a carefully orchestrated, protein-rich buffet.

These wildly different strategies underscore one core truth: motherhood in the animal kingdom isn’t a one-size-fits-all role. It’s shaped by ecology, physiology, and evolutionary pressures. Whether that means guarding eggs with your life or trusting nature to take its course, each approach has been honed by millions of years of trial and error. Motherhood, it turns out, is as adaptable and diverse as life itself.

In the animal kingdom, just like in human families, there’s no single rulebook for how to be a good mom. Some species take the “helicopter parent” route, staying close, responding to every cry and lavishing care on their young. Others prefer a more hands-off strategy, letting their little ones learn through life’s hard knocks. And surprisingly, both styles can be equally successful depending on the environment. Biologists use a handy framework called r/K selection theory to explain this spectrum of parenting [6]. It’s not about judgment; there’s no “right” or “wrong” here, but rather an evolutionary lens to understand why moms of different species do what they do. On one end, r-selected species, like mice, rabbits, and many insects, are the prolific producers of the animal world. They have lots of offspring, often at a young age, and invest relatively little in each individual. The idea is that with sheer numbers, a few are bound to make it. These moms operate on a strategy of “hope for the best” and sometimes, with enough babies, that works out just fine. On the other end of the scale are K-selected species, which include elephants, primates, whales, and other long-lived animals. These species have fewer babies, but invest heavily in each one through extended gestation, nursing, protection, and social learning. It’s a quality-over-quantity model.

One charming example of intensive maternal care comes from Orangutans. Their extraordinary mothers who invest in their offspring for many years, often more than a decade. During this extended period, they actively teach their young vital life skills such as how to find food, use tools, and build nests, thus building an essential foundation for survival in the forest [7]. Of course, not every animal opts for the hands-on route. Some moms, like the sea turtles, go for maximum output and minimal oversight. But this isn’t neglect; it’s a strategy honed by evolution for their specific lifestyle. In unpredictable environments, it makes more sense to bet on numbers rather than nurture. Neither is universally better, they’re just different adaptations to different environments. So whether a mom is wrapping her young in warm fur, delivering snacks to tree-dwelling tadpoles, or simply trusting nature to do its thing, she’s doing what evolution has equipped her to do best. As in human life, love and survival come in many forms, and each one tells us something remarkable about the power and flexibility of motherhood.

While some moms go it alone, others have backup. Across the animal kingdom, maternal care often becomes a team sport. If you’ve ever relied on a babysitting grandparent, a helpful partner, or that saintly friend who brings over snacks when you’re sleep-deprived, you’re not alone – evolution has your back. Many animals have evolved alloparenting: a system where individuals other than the biological mother pitch in to help raise the young. These helpers can be siblings, dads, aunties, or just well-meaning group members. And the benefits include longer survival, better-fed babies, and some much-needed “me time” for mom. Take the prairie vole (Microtus ochrogaster) for example, a small rodent with a surprisingly big heart. Prairie vole moms are the gold standard of attentive parenting: they build elaborate nests, spend hours grooming and nursing their pups, and show remarkable sensitivity to their babies’ needs [8]. And they don’t do it alone – prairie voles are one of the rare mammalian species where dads step up too, with both parents working together to raise their young. If animal behavior had a PTA, these voles would be co-presidents. Also in the running, meerkats, desert dwellers with a strict social structure. In a typical meerkat mob, it’s usually the dominant female who gives birth, but the entire clan gets involved in raising the pups. Subordinate females and males babysit, groom, and even provide food for the young [9]. It’s not just altruism; helpers gain valuable parenting experience, and by supporting their relatives, they’re boosting the chances that their shared genes survive. Meerkat daycare is both adorable and strategic. Then there are bonobos, our peaceful primate cousins. In bonobo communities, motherhood is rarely a solo act. Female bonobos form strong alliances and often support each other during child-rearing, especially when it comes to foraging, protection, and play [10]. These bonds aren’t just practical – they’re emotional too, helping to reduce stress and strengthen social cohesion. Bonobo moms lean on each other the way human moms might lean on a trusted friend.

Interestingly, this kind of cooperative breeding might not be so different from what shaped human evolution. Anthropologist Sarah Blaffer Hrdy has long argued that our ancestors likely survived thanks to shared parenting duties, with grandmothers, aunties, and even unrelated community members lending a hand [11]. In this view, the classic “it takes a village” isn’t just a saying; it’s a deeply rooted survival strategy that allowed human mothers (and their kids) to thrive. So next time you see a group of lionesses sharing cub duty or a group of apes passing around a baby like a fuzzy football, remember parenting doesn’t always have to be a solo journey. Sometimes, the best moms are the ones who know how to ask for help, and the best communities are the ones that step in without being asked.

So what actually turns a creature into a mother? What flips the switch from “independent individual” to “devoted caregiver”? As it turns out, motherhood is just as much about biochemistry as it is about behavior; it’s a full transformation that starts in the brain. During pregnancy and after birth, mammals undergo dramatic neurobiological changes that prime them for nurturing. Hormones like oxytocin surge, playing a key role in bonding and caregiving. Often called the “love hormone,” oxytocin helps mothers feel connected to their offspring and motivates them to keep those tiny, squirmy, demanding babies alive and thriving [12]. These changes aren’t just hormonal – the maternal brain physically reshapes itself! Areas like the amygdala (which processes emotion) and the prefrontal cortex (which handles decision-making and empathy) become more responsive to baby cues, from cries to smells to facial expressions [13]. As a result, moms become more attuned, more responsive, and sometimes more anxious, all part of a finely tuned system meant to keep offspring safe. So that infamous “mom brain” means keys might go missing and names get mixed up, but research suggests these cognitive shifts aren’t a malfunction – they’re side effects of a major mental reorganization. Studies show that motherhood may actually enhance long-term memory, emotional intelligence, and social awareness (Barha & Galea, 2017). The maternal brain isn’t losing steam – it’s just multitasking like crazy.

From the self-sacrificing octopus to the doting prairie vole, from the relaxed sea turtle to the communal meerkat, motherhood in nature is nothing if not diverse. There’s no perfect mom – only strategies honed over millennia to give the next generation a shot at survival. So whether you’re celebrating a human mom, a mentor, or a mama bird in your backyard, take a moment this Mother’s Day to honor the biology and brilliance of motherhood, in all its forms. Science shows us there’s no one right way to mom, but there’s beauty in every one of them.

Author Sabrina Seaborn-Mederos is 5th-year PhD candidate in the UC Davis Animal Behavior Graduate Group. Sabrina studies the neurobiology of pair bonding in seahorses and prairie voles but started her love for research studying the mother-infant bond in cats at UC Davis’ school of Vet Med.

References:

[1] Trivers, R. L. (1972). Parental investment and sexual selection. In Sexual selection and the descent of man (pp. 136–179). Aldine-Atherton.

[2] Rocha, F., Guerra, A. and González, A. F. (2001). A review of reproductive strategies in cephalopods. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 76, 291-304. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1464793101005681

[3] Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Biology Institute: https://nationalzoo.si.edu/animals/american-alligator

[4] Miller, J. D. (1997). Reproduction in sea turtles. In P. L. Lutz & J. A. Musick (Eds.), The biology of sea turtles (Vol. 1, pp. 51–81). CRC Press. https://doi.org/10.1201/9780203737088

[5] Lee, P. C. (1987). Allomothering among African elephants. Animal Behaviour, 35(1), 278–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0003-3472(87)80234-8

[6] Summers, K., & McKeon, C. S. (2004). The evolution of parental care and egg size: A comparative analysis in frogs. Evolution, 58(3), 527–535. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2005.3368

[7] Pianka, E. R. (1970). On r- and K-selection. The American Naturalist, 104(940), 592–597. https://doi.org/10.1086/282697

[8] van Noordwijk, M. A., Sauren, S. E. B., Ahbam, N. A., Morrogh-Bernard, H. C., Atmoko, S. S. U., & van Schaik, C. P. (2008). Development of independence: Sumatran and Bornean orangutans compared. In C. P. van Schaik & S. A. Mitra Setia (Eds.), Orangutans: Geographic variation in behavioral ecology and conservation (pp. 189–204). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199213276.003.0012

[9] Ahern, T. H., & Young, L. J. (2009). The impact of early life family structure on adult social attachment in prairie voles. Developmental Psychobiology, 51(4), 304–311. https://doi.org/10.3389/neuro.08.017.2009

[10] Hodge, S. J., Manica, A., Flower, T. P., & Clutton-Brock, T. H. (2008). Determinants of Reproductive Success in Dominant Female Meerkats. Journal of Animal Ecology, 77(1), 92–102. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20143162

[11] Furuichi, T. (2011). Female contributions to the peaceful nature of bonobo society. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews, 20(4), 131–142. https://doi.org/10.1002/evan.20308

[12] Hrdy, S. B. (2009). Mothers and Others: The Evolutionary Origins of Mutual Understanding. Harvard University Press.

[13] Numan, M., & Young, L. J. (2016). Neural mechanisms of mother–infant bonding and pair bonding: Similarities, differences, and broader implications. Hormones and Behavior, 77, 98–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2015.05.015

[14] Kim, P., et al. (2010). The plasticity of human maternal brain: Longitudinal changes in brain anatomy during the early postpartum period. Behavioral Neuroscience, 124(5), 695–700. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020884

[15] Barha, C. K., & Galea, L. A. M. (2017). The maternal “baby brain” revisited. Nature Neuroscience, 20(2), 134–135. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.4473

[Edited by Isabel Kier]