Fatherhood in the animal kingdom often escapes the spotlight. Biology textbooks and evolutionary theories emphasize maternal care as the default, while male animals were frequently cast as disengaged, uninvolved, or expendable. However, a closer look at the science tells a much richer story where animal dads are anything but background characters.

From penguins that brave months of starvation to protect their eggs, to fish that give birth, fatherhood across the animal kingdom is diverse, fascinating, and often heroic in ways that would put your favorite sitcom dad to shame. While evolutionary theory has long suggested that males typically invest less in offspring, plenty of species flip that script entirely. This Father’s Day, we’re giving center stage to the dads of the natural world: the solo caretakers, the tag-team partners, the fierce protectors, and the surprisingly snuggly. Because when it comes to being a good dad, nature shows us there’s no one-size-fits-all model – just strategies, instincts, and hormones fine-tuned across generations to give kids (or cubs or tadpoles) their best shot.

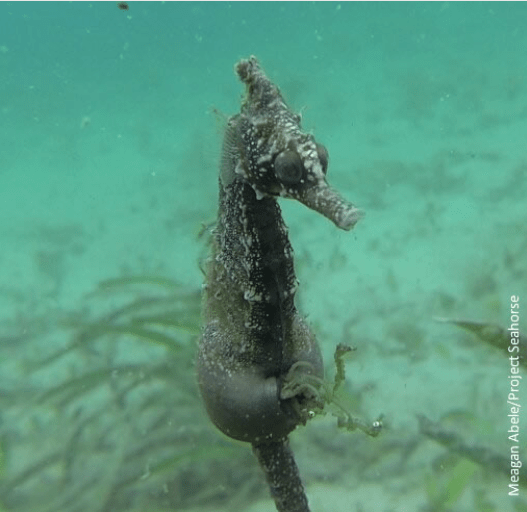

While humans often debate over chore charts and parenting roles, in some animal species, fatherhood is less of a partnership and more of a solo act. These devoted dads don’t just help out – they carry the entire team. Take the seahorse, for example. In one of nature’s most famous role reversals, it is the male who gets pregnant. After a female transfers her eggs into the male’s brood pouch, he fertilizes them internally and carries the developing embryos until birth. He regulates salinity, provides oxygen, and contracts his body to deliver the offspring, sometimes hundreds in a single brood [1]. That’s not just support, that is literally taking on the labor! Then there is the emperor penguin, whose parenting style includes balancing a fragile egg on his feet through the brutal Antarctic winter. For more than two months, the male incubates the egg without eating, relying entirely on stored fat while temperatures plunge below minus 40 degrees Celsius [2]. In Jacanas, a group of tropical shorebirds distributed across multiple continents, the males do most of the offspring care [3]. If a threat approaches, the lily-trotting jacana dad scoops up his offspring and nestles them quite literally under his wing, leaving only a couple extra sets of legs and toes dangling out as evidence, as he hustles them to safety. This is the avian version of a stay-at-home superdad. The amphibious equivalent is the coquí. The female coquí can lay on average 26 eggs, all of which end up in the exclusive care of the male coquí, and they take this job very seriously. The male coquí places himself above the eggs and spends on average 97.4% of his time during the day and 75.8 % of his time during the night directly protecting the clutch with his body, often forgoing meals. When necessary, the male coquí will also fight potential predators, despite not having teeth. These dads are so good at their job that their clutches on average have about a 77.5% success rate. That is to say that most of their eggs hatch into adulthood [4]. Even in the primate world, some fathers do the heavy lifting. Titi monkeys, small New World primates known for strong pair bonds, rely heavily on paternal care. The father carries the infant nearly all the time, handing it to the mother only for nursing. Studies show that this constant contact strengthens the bond between father and offspring [5]. These species remind us that fatherhood is not defined by biology alone. Across the animal kingdom, many dads are not just involved -they are essential.

Parenting in the animal kingdom is often a team effort, with dads playing crucial roles alongside moms. These dynamic duos demonstrate how cooperative care boosts offspring survival and social bonding. Many species rely on both parents for raising the next generation. Take California mice, for example. Like their prairie vole cousins mentioned in the mother’s day article, California mouse fathers are highly involved, engaging in behaviors such as pup retrieval, licking, and huddling to keep their young warm and safe. Research has shown that paternal care in this species is crucial for healthy pup development and stress regulation [6]. In the aquatic realm, monogamous cichlid fish engage in biparental care where both parents guard and fan the eggs, protect fry, and even teach their offspring to forage. Studies indicate that paternal involvement improves offspring growth and survival rates [7].These examples showcase the diversity of cooperative parenting strategies. Whether on land, in water, or in trees, many species prove that teamwork between moms and dads is an evolutionary winning formula.

Raising offspring can sometimes look like a group project, with multiple males and helpers contributing to the well-being of the young. This group effort often enhances survival chances and strengthens social bonds within the group. Consider lion coalitions, where related males team up to protect a pride. These coalition members fiercely guard cubs from rival males that might kill offspring to bring females back into heat. Beyond protection, males support the pride’s territory defense and hunting efforts, indirectly boosting cub survival [8]. Here, fatherhood is as much about team defense as it is about individual care. In wolf packs, pups benefit from a network of caregivers. Both parents and helpers, often older siblings or ‘uncles’, share duties such as feeding, guarding, and teaching pups vital survival skills. This cooperative care ensures pups receive constant attention and protection, reflecting a social structure where parenting is distributed across the family group [9].These examples underscore that in nature, many dads thrive in a community, proving that it often takes a village to raise a child.

Fatherhood comes with biological transformations that shape behavior and brain function. Like mothers, many animal dads experience hormonal and neurological shifts that prepare them for the demands of parenting. One hormone often linked to nurturing behavior is prolactin. Originally studied for its role in lactation, prolactin also influences paternal care across birds and mammals. For example, male birds with elevated prolactin levels show increased nest building and feeding of chicks, while in mammals it promotes nurturing behaviors and even physical changes like testicular regression during parenting [10]. The neuropeptides vasopressin and oxytocin are critical modulators of paternal bonding, especially in monogamous species. Vasopressin in particular has been associated with paternal aggression, territorial defense, and bonding in species like prairie voles. Oxytocin enhances social recognition and caregiving motivation, strengthening the emotional connection between fathers and offspring [11]. Parenting also triggers neural plasticity which is the brain’s ability to reorganize itself. Human fathers, for example, exhibit changes in brain regions involved in emotion regulation, empathy, and motivation, including the prefrontal cortex and amygdala. These adaptations support attentive and responsive caregiving behaviors [12]. Together, these hormonal and neural changes create a finely tuned “dad brain,” perfectly designed to meet the challenges and joys of fatherhood.

Fatherhood in the animal kingdom reveals a remarkable spectrum of care, commitment, and cooperation. From the devoted seahorse dads who carry their young to term, to the cooperative coalitions of lions and wolves protecting their kin, male parents display an extraordinary variety of strategies shaped by evolution. These diverse examples remind us that fatherhood is an adaptive response suited to different ecological and social environments. The biological shifts in hormone levels and brain plasticity that accompany paternal care highlight the deep connection between physiology and behavior. Fatherhood is as much a transformation of the mind as it is a change in daily routine. Understanding these processes not only enriches our appreciation of animal behavior but also offers insights into the complex nature of human fatherhood. This Father’s Day, as we celebrate dads of all species, let us marvel at the many ways fathers contribute to nurturing the next generation.

Author Sabrina Seaborn-Mederos is 5th-year Ph.D candidate in the UC Davis Animal Behavior Graduate Group. Sabrina studies the neurobiology of pair bonding in seahorses and prairie voles, both great examples of animal fathers! Big thank you to contributors Alice Michel, Sofía Meléndez Cartagena, and Nicole Rodrigues for their suggestions on great fathers!

References:

[1] Foster, S. J., & Vincent, A. C. J. (2004). Life history and ecology of seahorses: Implications for conservation and management. Journal of Fish Biology, 65(1), 1–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-1112.2004.00429.x

[2] Stonehouse, B. (1953). The Emperor Penguin (Aptenodytes forsteri, Gray): I. Breeding behaviour and development (FIDS Scientific Report No. 6). HMSO.

[3] Miller, A. H. (1931). Observations on the incubation and the care of the young in the Jacana. Condor, 33(1), 14.

[4] Townsend, D. S., Stewart, M. M., & Pough, F. H. (1984). Male parental care and its adaptive significance in a neotropical frog. Animal Behaviour, 32(2), 421–431.

[5] Fernandez-Duque, E., Valeggia, C. R., & Mendoza, S. P. (2009). The biology of paternal care in human and nonhuman primates. Annual Review of Anthropology, 38, 115–130. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-091908-164334

[6] Trainor, B. C., and C. A. Marler. (2001). Testosterone, Paternal Behavior, and Aggression in the California Mouse. Hormones and Behavior 40(1), 32–42.

[7] Wisenden, B. D. (1995). Reproductive behaviour of free‑ranging convict cichlids, Cichlasoma nigrofasciatum. Environmental Biology of Fishes, 43(2), 121–134. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00002480

[8] Packer, C., and A. E. Pusey. (1983). Adaptations of Female Lions to Infanticide by Incoming Males. American Naturalist 121(5), 716–728. https://doi.org/10.1086/284097

[9] Bangs E. E. (2004). Wolves: Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation. Journal of Mammalogy 85(4), 815. https://doi.org/10.1644/1545-1542(2004)085<0815:BR>2.0.CO;2

[10] Ziegler, T. E. (2000). Hormones Associated with Non-Maternal Infant Care: A Review of Mammalian and Avian Studies. Folia Primatologica, 71(1-2), 6-21. https://doi.org/10.1159/000021726

[11] Bales, K. L., and C. S. Carter. 2003. “Developmental Exposure to Oxytocin Facilitates Partner Preferences in Male Prairie Voles.” Hormones and Behavior 44(2): 229–236. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7044.117.4.854

[12] Grande, L., Tribble, R., Kim, P. (2020). Neural Plasticity in Human Fathers. In: Fitzgerald, H.E., von Klitzing, K., Cabrera, N.J., Scarano de Mendonça, J., Skjøthaug, T. (eds) Handbook of Fathers and Child Development. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-51027-5_11

[Edited by: Isabel Kier]