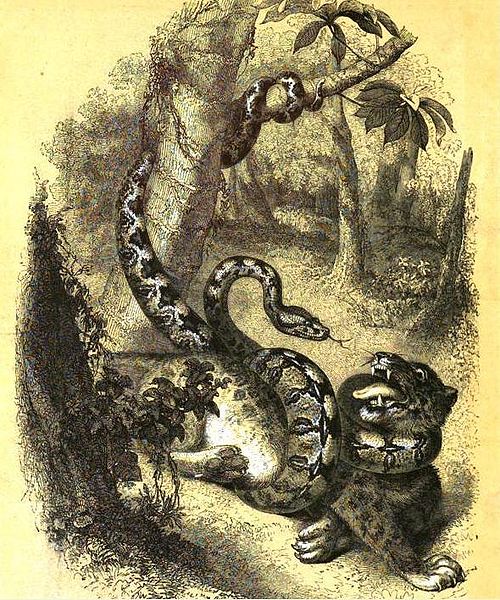

What comes to mind when you hear the word, “boa?” Perhaps you are envisioning a three-meter-long snake in the Amazon Rainforest – a formidable predator that eats sweet little monkeys and hapless possums. You wouldn’t be alone on this train of thought. Indeed, even Charles Darwin’s co-discoverer of natural selection, Alfred Russel Wallace, had an exaggerated impression of snakes from this family. In his 1878 essay entitled Animal Life in the Tropical Forests, he wrote the following about the largest of boas, the Green Anaconda [1]:

“The great water-boa of South America is believed to reach the largest size. Mr. Bates measured skins twenty-one feet long, but the largest ever met with by a European appears to be that described by the botanist, Dr. Gardiner, in his Travels in Brazil. It had devoured a horse, and was found dead, entangled in the branches of a tree overhanging a river, in which it had been carried by a flood. It was nearly forty feet long. These creatures are said to seize and devour full-sized cattle on the Rio Branco; and from what is known of their habits this is by no means improbable.”

Sorry, Mr. Wallace, and with all due respect, you seem to have gotten your facts on this subject a bit jumbled. While these snakes do sometimes attain lengths in the neighborhood of 20 feet, these early accounts of their size (and diet) are certainly dubious. People tend to exaggerate the size of intimidating animals, both in their perceptions and in recounting their experiences. However, the fact that these serpents are impressive cannot be denied.

Would you now be surprised to learn that there are native boas in Western North America? In fact, boas can be found in mountain ranges from frigid British Columbia, through the Western United States, and, throughout Mexico. Are you now worried that the family dog will be snapped up by a huge snake during a weekend hike in the woods? Before your mind conjures up more scenarios of the ophidiophobic (snake-fearing) kind, rest assured that this will surely never happen. Imagine that you are strolling through a coastal California forest and happen upon one of these snakes making its way across the trail. Take the serpentine behemoth from your mind’s eye and shrink it down to a total length of about two feet and about as thick as your thumb. Color it chocolatey brown and round out the features of its face and tail. Imagine it plugging along at roughly the same pace as honey pours from a jar. Once you have made these adjustments, you will have quite an accurate image of a Northern Rubber Boa (Charina bottae).

These petite members of the boa family are quiet and secretive creatures, and human observers can count themselves lucky (and quite safe!) if they encounter one. In regard to their name – their brown, glossy skin does indeed result in a somewhat rubbery appearance. But perhaps one of their other common names, the Two-headed Snake, is a more interesting descriptor. This snake features a notably rounded tail, so blunt that it might be difficult to tell which end is which at first glance. In fact, this blunt tail serves as one of its primary defense mechanisms [2]. When threatened by a rodent defending its nestlings or by a predatory bird, this little boa will protect its head beneath the coils of its body and expose its blunt-ended tail, even waving it about. Animals are often fooled by this display and attack the wrong end, leaving the snake with a minor injury to its tail, rather than a life-threatening blow to the head. Most Northern Rubber Boas bare scars on the back ends of their bodies that attest to the effectiveness of this ploy.

The adaptations facilitating this defensive behavior run more than skin-deep. If you put a rubber boa under an x-ray, you would see that the tail doesn’t taper off into increasingly small caudal (tail) vertebrae like most other snakes. Instead, you would notice that the skeleton ends with an almost club-shaped cluster of vertebrae. The end of the tail is highly ossified (reinforced with extra bone), offering a further level of protection to this animal [3]. Its specialized behavior and morphology are intimately intertwined.

Another interesting aspect of this snake’s biology is its relative tolerance of cool temperatures. While most snakes don’t like the scorching heat that many people assume they do, the Northern Rubber Boa can take things quite far in the other direction. Snakes are ectothermic (what is usually [and imprecisely] referred to as being cold-blooded). As such, they depend on heat from the environment to regulate their body temperatures. For most snakes, this means that they will scarcely have the energy to move once they fall much below about 15°C (~60°F). In contrast, the Northern Rubber Boa seems to be particularly cold tolerant among serpents, and is known to be surface active at temperatures as low as 10°C (50°F). Although the mechanism needs further study, there is evidence that these snakes are able to physiologically increase their rates of warming and reduce their rates of cooling [4]. Furthermore, a study of temperature differences across body regions in this species showed that when they are too warm, they can maintain their head at a lower temperature than the rest of their body. Similarly, they can concentrate warmth in their head when they are too cool [5]. The Northern Rubber Boa demonstrates that there is not a black and white difference between ‘cold’ and warm-blooded animals.

The Northern Rubber Boa slithers against the grain, defying what most people imagine a snake, and especially a boa, to be like. They are small, slow, placid and, most of all, delightful.

Main featured image by Brandon R. Kong.

Written by: Brandon R. Kong is a PhD student in the Fischer Lab and the Animal Behavior Graduate Group at UC Davis. He worked on salamander natural history and conservation genetics as an undergraduate at UC Santa Cruz, and on reptile physiology during his MS at Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo. Now, he is beginning to explore the convergent evolution of parental care in amphibians.

References:

[1] Wallace, A. R. (1878). Animal Life in the Tropical Forests. Pp. 69–123 in Wallace, A. R. Tropical Nature and Other Essays. Macmillan and Co. London.

[2] Hansen, R. W., Shedd, J. D. (2025). California Amphibians and Reptiles. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

[3] Greene, H. W. (1973). Defensive Tail Display by Snakes and Amphisbaenians. Journal of Herpetology, 7(3), 143–161, https://doi.org/10.2307/1563000

[4] Zhang, Y., Westfall, M. C., Hermes, K. C., Dorcas, M. E. (2008). Physiological and behavioral control of heating and cooling rates in rubber boas, Charina bottae. Journal of Thermal Biology 33, 7–11, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtherbio.2007.08.005

[5] Dorcas, M. E., Peterson, C. R. (1997). Head-body Temperature Differences in Free-ranging Rubber Boas. Journal of Herpetology 31(1), 87–93, https://doi.org/10.2307/1565333

[Edited by Jacob Johnson and Alice Michel]