Growing up in New York State, I knew turtles as slow creatures, bell-shaped and rugged, with the wrinkled face and lumbering demeanor of a wise old man. One or two might inhabit your backyard, or be found swimming in a nearby pond. In comparison to these terrestrial and freshwater specimens, sea turtles were a distant other that I would never encounter in my landlocked town. It was Master Oogway from Kung Foo Panda vs. Crush from Finding Nemo; one impossibly ancient, the other immortally cool. Like Nemo, I was dying to meet a sea turtle in real life. This fall, I jumped at the opportunity to spend a semester abroad on the small island of Losinj, Croatia, studying Adriatic marine megafauna at the Blue World Institute (BWI). Three months of close contact with live sea turtles at the BWI’s Turtle Rescue Center taught me that, while they are not immortal beings, they are an exceptionally unique and resilient group of animals.

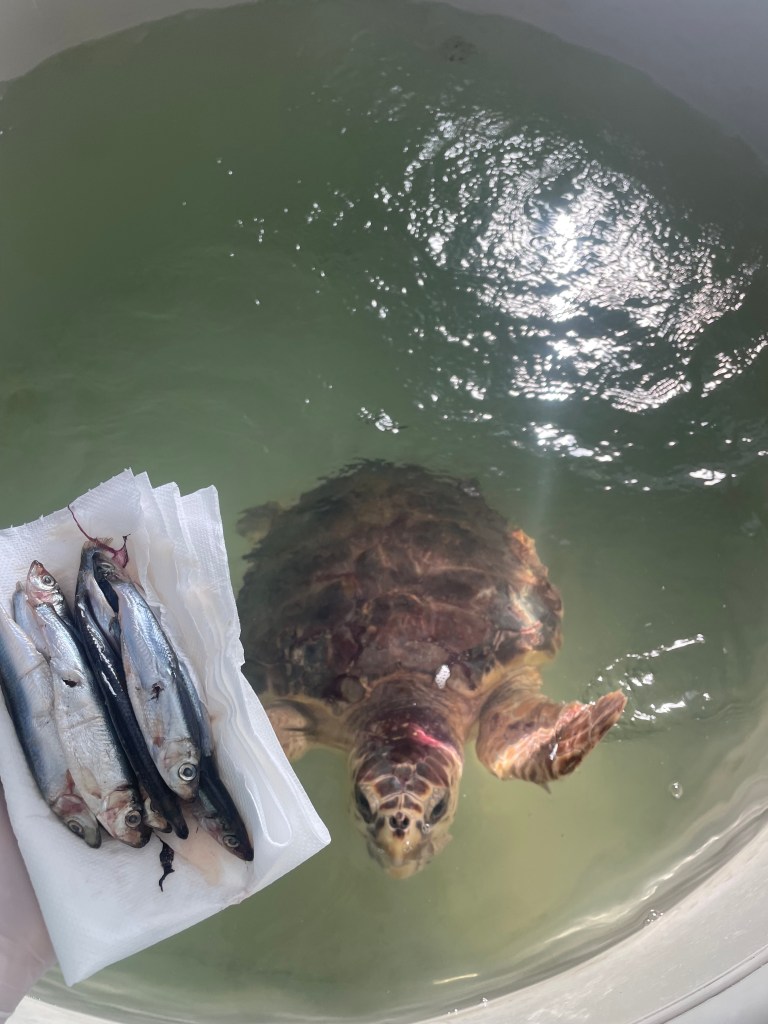

Photo by Maya Blanchard.

The word “turtle” refers to the overarching order Testudines, a group of oviparous (egg-laying) reptiles with a unique shell called a carapace. Their geometrically-patterned plates, or scutes, are made of keratin: the same material as our fingernails! Unlike other hard-shelled animals that grow bony armored plates from their skin (think armadillos or pangolins), turtles’ carapaces evolved from a flattened, broadened ribcage and are therefore fused directly to their skeletons [1, 2].

A few key characteristics, a result of adapting to life in a marine environment, set sea turtles apart from their terrestrial cousins. The sea turtles that live on Earth today are split into two main families: Cheloniidae, which includes the loggerhead (Caretta caretta), green (Chelonia mydas), olive ridley (Lepidochelys olivacea), Kemp’s ridley (Lepidochelys kempii), flatback (Natator depressus), and hawksbill (Eretmochelys imbricata) turtles; and Dermochelyidae, which includes only the leatherback turtle (Dermochelys coriacea). The carapaces of Cheloniidae turtles are less domed than their terrestrial counterparts, and their front and hind legs have been modified into flippers. These hydrodynamic modifications allow sea turtles to gracefully glide through the water with little resistance. Leatherback turtles are similarly streamlined, but a thick skin covers their back in lieu of a hard shell.

A tradeoff for a more hydrodynamic carapace is the inability to retract their heads for protection as tortoises can [3]. As an alternative protection strategy, sea turtles have evolved to be very large. Leatherbacks, lacking any hard protection, are the largest of them all: a useful defense against their main predator, the killer whale. Tiger sharks also prey on sea turtles since their strong jaws can cut through the tough carapace, but turtles often evade attacks by using their shells as a shield or flipping onto their back (see below). The greatest threat to sea turtles is human activity: in the Adriatic alone, an estimated 5,000 turtles are caught in trawling nets each year, putting them at risk of entanglement, blunt force trauma, and drowning [4]. With proper care, like the kind given at the Rescue Center, turtles found in an emaciated state can make full recoveries and be released!

A loggerhead sea turtle demonstrates predator evasion tactics when confronted with a tiger shark in Australia.

Sea turtles are famous for their great migrations, sometimes traveling over a thousand miles in one lifetime. The secret to their impeccable navigation is magnetoreception: an innate ability to sense Earth’s magnetic field [5]. Hatchlings use their “internal compass” to find their way from their sandy nests to the shore. They make the journey at night in order to avoid daytime predators, such as crabs and birds. Once in the water, they swim in a frenzy until strong currents transport them to deeper waters, a phase of life known to scientists as the “Lost Years”, since it’s nearly impossible to find a tiny turtle in the open ocean [6].

As their lives go on, sea turtles continue to use magnetoreception [5]. The unique magnetic fields of different geographic areas guide young turtles through the deep ocean to neritic (nearshore) foraging grounds. With the exception of leatherbacks, who stay in open water for the majority of their life, juvenile turtles live near the shore, feed on benthic prey, and build a “magnetic map” of their foraging grounds as they learn the terrain [7]. Their magnetic sense helps them migrate again for breeding once they reach maturity, this time to tropical or subtropical nesting beaches. Sea turtles display high nesting site fidelity, meaning they lay their clutch on the same beach they hatched from [8]! Female sea turtles lay their eggs under cover of darkness, avoiding the sun’s hot rays and the dangerous daytime predators. The flipper tracks that mothers leave in the sand as they drag their way up the beach are unique to their species, helping scientists pinpoint where different turtles nest.

Sea turtles’ migratory nature makes them difficult to study and even harder to conserve. The IUCN Red List recognizes the leatherback and Kemp’s ridley turtles as Critically Endangered worldwide, with the other species being either Endangered, Vulnerable or Data Deficient [9].

Photo by Maya Blanchard.

Luckily, an increase in satellite telemetry data is expanding our global map of sea turtle pathways and solidifying conservation efforts between coastal countries. Adelita the loggerhead shattered scientists’ expectations 20 years ago when she became the first sea turtle to be satellite tracked all the way from Mexico to Japan, inspiring the creation of the Loggerhead STRETCH collaborative research and conservation program between the two countries. Scientists have even leveraged new telemetry technology to satellite track juvenile and neonatal turtles, a huge step in filling the knowledge gap of the Lost Years [6].

Photo by Maya Blanchard.

In exciting positive news, the number of loggerhead nesting sites in the Mediterranean has increased in recent years, leading to the down-listing of the resident population to Least Concern. However, the species as a whole is still considered Vulnerable, and even Mediterranean loggerheads continue to be highly conservation-dependent due to the consistent monitoring and rehabilitation work required to ensure their status [10]. Nevertheless, this shows that conservation and research can dramatically improve outcomes for sea turtle populations. Continued efforts to understand and protect sea turtles are imperative to insure they do not fade into myth and instead remain as they are: real, resilient, and immortally awesome.

Main featured image: A Green Sea Turtle (Chelonia mydas) in Sipidan, Malaysian Borneo. Photo by Jesse Schoff [Source].

Written by: Maya Blanchard is a senior at Cornell University studying Biological Sciences with a concentration in Marine Biology. She can be reached at mhb237@cornell.edu.

References:

[1] Li, C., Wu, X. C., Rieppel, O., Wang, L. T., & Zhao, L. J. (2008). An ancestral turtle from the Late Triassic of southwestern China. Nature, 456(7221), 497-501.

[2] Hirasawa, T., Nagashima, H., & Kuratani, S. (2013). The endoskeletal origin of the turtle carapace. Nature Communications, 4(1), 2107.

[3] Wyneken, J. (2001) The anatomy of sea turtles: Part II. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-SEFSC-470. U.S. Department of Commerce, pp. 53–112.

[4] Mihaljević, Ž., Naletilić, Š., Jeremić, J., Kilvain, I., Belaj, T., & Andreanszky, T. (2024). Spatiotemporal Analysis of Stranded Loggerhead Sea Turtles on the Croatian Adriatic Coast. Animals, 14(5), 703.

[5] Lohmann, K.J. (2007) ‘Sea turtles: navigating with magnetism’, Current Biology, 17(3), pp. R102–R104. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2006.12.017.

[6] Mansfield, K. L., Wyneken, J., Porter, W. P., & Luo, J. (2014). First satellite tracks of neonate sea turtles redefine the ‘lost years’ oceanic niche. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 281(1781), 20133039.

[7] Goforth, K. M., Lohmann, C. M., Gavin, A., Henning, R., Harvey, A., Hinton, T. L., … & Lohmann, K. J. (2025). Learned magnetic map cues and two mechanisms of magnetoreception in turtles. Nature, 638(8052), 1015-1022.

[8] Broderick, A. C., Coyne, M. S., Fuller, W. J., Glen, F., & Godley, B. J. (2007). Fidelity and over-wintering of sea turtles. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 274(1617), 1533-1539.

[9] Wallace, B.P., Tiwari, M. and Girondot, M. (2013) Dermochelys coriacea. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2013: e.T6494A43526147. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-2.RLTS.T6494A43526147.en (Accessed: 5 January 2026).

[10] Hutchinson, B. (2020) ‘The conservation status of loggerhead populations worldwide’, State of the World’s Sea Turtles (SWOT), 6 July. https://www.seaturtlestatus.org/articles/2017/the-conservation-status-of-loggerhead-populations-worldwide (Accessed: 5 January 2026).

[Edited by Alice Michel]