Valentine’s Day is approaching, which means science media is going to once again be filled with awww-inducing images of penguins standing shoulder-to-shoulder and seahorses delicately entwining their tails, usually accompanied by claims about “mating for life.” These stories are comforting, romantic, and… deeply misleading. The reality of animal “love” is far more nuanced. Animal attachment is rare. Most animals do not form long-term relationships, and even fewer develop selective psychological attachments to a partner. What is often described as “love” is usually a misunderstanding of monogamy, which in biology refers not to emotion, but rather the strategy of repeated mating with the same individual across multiple breeding cycles. Monogamy describes who mates with whom, not how individuals feel about each other. The emotional component, when it exists, is known as a pair bond, a selective attachment between individuals in a mating pair characterized by a number of features that tell us how attached they are to one another [1].

As someone who studies pair bonds, I’m often asked the age-old question: How do you know they’re attached? It’s a fair question. I can’t ask a prairie vole how it feels. I can’t check a seahorse’s relationship status or watch them exchange Valentine’s Day cards. But attachment leaves evidence. It shows up in behavior; who animals associate with, who they avoid, how they respond to stress, and what happens when their partner disappears. To make sense of these behavioral signatures, it helps to borrow a framework some of us already understand: reality TV. Because like animal relationships, reality-show relationships are shaped by limited information, competition, stress, proximity, and environmental pressure. And just like animals, contestants often reveal attachment not through grand declarations, but through what they do when conditions get difficult. Because if there’s one thing reality TV shows have taught us, it’s that relationships are rarely neat, often strategic, occasionally chaotic, and always shaped by the environment around them. Animals, as you’ll see, aren’t so different.

Mate Choice — Love Is Blind

Mate choice is the very first step in the process of forming a pair bond. While you might think love at first sight applies to animals, attachment doesn’t begin with love, it begins with assessment. It’s a social cognitive process that encompasses mechanisms for acquiring, processing, retaining and acting on social information. It involves both assessing other individuals and their condition (e.g., health, infection status) and deciding about when and how to interact with them [2]. This process closely mirrors the premise of the reality TV classic Love Is Blind, where contestants are unable to see their social partners and thus must form connections based on limited information such as their voice and their conversations, while simultaneously competing with others for the same partners. Animal mate choice unfolds under similar constraints. Individuals detect and identify one another using available sensory cues, including olfactory, auditory, tactile, and visual signals, with the relative importance of each modality varying by species and ecological context. For example, rodents rely heavily on olfactory cues to assess potential mates [3,4], where primates and many birds place greater weight on visual signals such as facial features, coloration, or display behaviors [5,6].

Crucially, this evaluation rarely happens in isolation. Mate choice often unfolds in highly competitive social environments where multiple individuals vie for attention and access to the same partners. A striking example comes from lekking species such as sage grouse, while they are not a pair-bonding species, males do congregate in display arenas and engage in intense competition through vocalizations, postures, and repeated courtship displays. Despite the presence of many competitors, females consistently select only a small subset of males, making mate choice a process shaped as much by rivalry and relative comparison as by individual traits [7]. Standing out in these contexts requires not perfection but being just a bit more attractive than the sage grouse next to you.

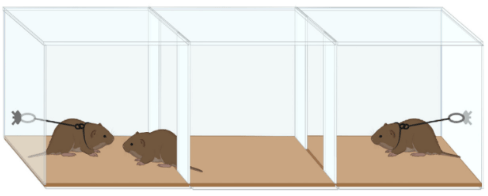

Partner Preference — The Ultimatum

A defining feature of a pair bond is selective partner preference. In The Ultimatum, commitment is revealed not by words, but by who someone chooses to be with when alternatives are available. Researchers test animal attachment the same way. The first component of partner preference is mate recognition; an animal has to be able to distinguish their partner from everyone else. In classic partner-preference tests, prairie voles given a choice between their partner and a stranger consistently choose to spend more time in physical proximity to their partner and engaging in pro-social behavior like huddling, even when the stranger is novel or sexually receptive [1,8]. This preference is one of the strongest behavioral indicators of a pair bond. It tells us that love, biologically speaking, is sometimes about deliberate choice when faced with alternative options.

Stress Buffering & Distress Upon Separation — Love Island

On Love Island, being in a couple offers protection: emotional support, physical closeness, and social safety. Singles are more vulnerable, more anxious, and more likely to be eliminated. If a contestant’s partner is coupled up with someone else, it’s shown to cause a lot of distress (fans will remember Huda’s big reaction!). Animals show strikingly similar patterns. In bonded prairie voles, the presence of a partner dampens stress responses, reducing corticosterone release during stressful events [9]. When partners are separated, bonded individuals show increased anxiety-like behavior, elevated stress hormones, and disrupted sleep and feeding patterns [10]. Stress buffering and separation distress are hallmarks of true attachment across species. Through this, attachment is revealed both when partners are together, and also when they’re forced apart.

Mate Guarding & Directed Aggression — Jersey Shore

Attachment isn’t always gentle. In many species, a rough edge is an important part of long-term relationship stability. After forming a pair bond, animals often show selective aggression toward unfamiliar rivals, a phenomenon frequently mislabeled as jealousy but more accurately described as mate guarding. This aggression is not indiscriminate; it is targeted, context-dependent, and emerges specifically after attachment has formed. In prairie voles, males that have established a pair bond become markedly more aggressive toward unfamiliar conspecifics while remaining affiliative and tolerant toward their partner [11]. It’s a striking contrast: the same animal that huddles calmly with its mate may moments later respond aggressively to a stranger of the opposite sex. Similar patterns appear across taxa. In many birds and fish, bonded individuals defend mates and shared territories more intensely than unpaired individuals, particularly when potential rivals are present [12]. Far from undermining attachment, this aggression helps protect it.

If this sounds familiar, it’s because we’ve all seen a version of it play out on Jersey Shore. Anyone with unfiltered cable access in the early 2010s remembers the chaos: romantic entanglements, territorial disputes, and explosive confrontations over who was talking, or dancing, with whom. Placing multiple attractive, socially competitive individuals in a confined space wasn’t accidental; it was a recipe for conflict. Attraction created attachment, and attachment created boundaries. When those boundaries were crossed, aggression followed. Animals operate under similar rules. When pair bonds form in crowded or competitive social environments, aggression toward outsiders can serve a stabilizing function. It reduces interference, discourages rival mating attempts, and reinforces partner exclusivity. In both animal societies and reality TV houses, relationships don’t exist in a vacuum, they exist in social landscapes where competition is unavoidable. Stability, it turns out, often requires conflict.

Behavioral Synchrony — Dancing With the Stars

Bonded pairs often move through the world together in a very literal sense. Coordinated behavior, known as behavioral synchrony, is a common feature of pair bonds across many species. In monogamous animals, partners align their daily activity patterns such as foraging, nesting, and resting, which can improve efficiency and reduce the risk of predation. Moving together allows pairs to anticipate one another’s actions and respond as a unit rather than as two independent individuals [13]. This synchronization does more than streamline daily life. It reflects a shared internal state that develops through repeated interaction and experience. Over time, bonded partners begin to match each other’s pace, timing, and decision making, reinforcing the attachment itself. Synchrony becomes both a consequence of bonding and a mechanism that helps maintain it. Rather than dramatic displays of affection, attachment is revealed through subtle coordination and mutual adjustment.

This dynamic is surprisingly easy to spot on shows like Dancing With the Stars. While the dancers are not romantic partners, their success depends on how well they can attune to one another. Technical skill matters, but compatibility often matters more. Pairs that listen, adapt, and move in sync tend to outperform those who cannot align their timing or respond fluidly to one another. The same principle applies in the animal world. For many species, attachment shows up in rhythm rather than romance. Seahorses provide a particularly elegant example of behavioral synchronization shaping the bonding process through literally dancing! In monogamous seahorse species, males and females engage in daily greeting rituals that include synchronized swimming, color changes, and coordinated movements often described as courtship dances. These repeated interactions help maintain pair bonds and synchronize reproductive timing between partners, particularly given the male’s role in pregnancy [14]. The dance itself is not decorative. It is functional, reinforcing coordination and trust between partners before reproduction occurs.

Courtship & Mating — The Bachelor / Bachelorette

Courtship rituals such as displays, repeated interactions, and mating behaviors are often mistaken for love itself. Biologically, however, they are better understood as bond building processes rather than evidence of attachment. Courtship provides opportunities for assessment, reinforcement, and coordination, allowing potential partners to gather information about one another while gradually strengthening social ties [15]. These behaviors are widespread across animal taxa and take many forms, from visual displays and vocalizations to gift giving and shared experiences. If this sounds familiar, it is because reality dating shows rely on the same logic. On The Bachelor or The Bachelorette, roses function as symbolic investments that signal interest and exclusivity, while repeated one on one dates serve to reinforce emerging connections. In the animal world, the medium may be different, but the structure is similar. Among penguins, courtship includes the offering of pebbles that are later used to construct shared nests. In Adélie penguins, males present stones to females during courtship, and pebble exchange continues throughout the breeding season as partners maintain and defend their nest together [16].

And then there is mating itself. In the world of reality TV, this is often reserved for the fantasy suite, framed as a private and pivotal moment that can deepen a relationship but does not guarantee commitment. Biologically, mating plays a similar role in many pair bonding species. In prairie voles, mating triggers neurochemical changes involving oxytocin, vasopressin, and dopamine that support the formation of a pair bond by linking social cues with reward processing [17]. Mating increases the likelihood of attachment, but it does not ensure it. Just as not every overnight date leads to a proposal, not every mating event results in a lasting bond. Courtship and mating, then, are best understood as opportunities rather than promises. They create the conditions under which attachment can form, but they are only one part of a much larger and more complex process.

Whether in a laboratory, the wild or a televised villa, relationships are tested through choice, conflict, coordination and separation. While we may not see them exchange roses or give confessional interviews, animals show us attachment through their behavior. They teach us about bonds when there are no cameras or language to hide behind, and this Valentine’s Day we honor the real depictions of animals who show love, not unlike the kind we see on TV.

Author Sabrina Seaborn-Mederos is 6th-year PhD candidate in the UC Davis Animal Behavior Graduate Group. Sabrina studies the neurobiology of pair bonding in seahorses and prairie voles and considers that enough expertise to watch and judge reality dating TV shows.

References:

[1] Bales, K. L., Ardekani, C. S., Baxter, A., Karaskiewicz, C. L., Kuske, J. X., Lau, A. R., Savidge, L. E., Sayler, K. R., & Witczak, L. R. (2021). What is a pair bond? Hormones and Behavior, 136, 105062. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2021.105062

[2] Kavaliers, M., & Choleris, E. (2017). Social cognition and the neurobiology of social recognition. Integrative and Comparative Biology, 57(4), 778–789. https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/icx042

[3] Luo, M., Fee, M. S., & Katz, L. C. (2003). Encoding pheromonal signals in the accessory olfactory bulb of behaving mice. Science, 299(5610), 1196–1201. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1082133

[4] Young, L. J., Lim, M. M., Gingrich, B., & Insel, T. R. (2011). Cellular mechanisms of social attachment. Hormones and Behavior, 59(1), 98–104. https://doi.org/10.1006/hbeh.2001.1691

[5] Osorio, D., & Vorobyev, M. (2008). A review of the evolution of animal colour vision and visual communication signals. Vision Research, 48(20), 2042–2051. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.visres.2008.06.018

[6] Waitt, C., Little, A. C., Wolfensohn, S., Honess, P., Brown, A. P., Buchanan-Smith, H. M., & Perrett, D. I. (2003). Evidence from rhesus macaques suggests that male coloration plays a role in female primate mate choice. Biology Letters, 270(Suppl 2), S144–S146. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2003.0065

[7] Gibson, R. M., & Bradbury, J. W. (1985). Sexual selection in lekking sage grouse: Phenotypic correlates of male mating success. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 18(2), 117–123. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00299040

[8] Williams, J. R., Catania, K. C., & Carter, C. S. (1992). Development of partner preferences in female prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster): The role of social and sexual experience. Hormones and Behavior, 26(3), 339–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/0018-506X(92)90004-F

[9] Smith, A. S., & Wang, Z. (2014). Hypothalamic oxytocin mediates social buffering of the stress response. Biological Psychiatry, 76(4), 281–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.09.017

[10] Bosch, O. J., Nair, H. P., Ahern, T. H., Neumann, I. D., & Young, L. J. (2009). The CRF system mediates increased passive stress-coping behavior following the loss of a bonded partner in a monogamous rodent. Neuropsychopharmacology, 34(6), 1406–1415. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2008.154

[11] Aragona, B. J., Liu, Y., Curtis, J. T., Stephan, F. K., & Wang, Z. (2003). A critical role for nucleus accumbens dopamine in partner-preference formation in male prairie voles. The Journal of Neuroscience, 23(8), 3483–3490. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03483.2003

[12] Kleiman, D. G. (1977). Monogamy in mammals. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 8, 39–69. https://doi.org/10.1086/409721

[13] Roth, T. S., Samara, I., Tan, J., & Prochazkova, E. (2021). A comparative framework of inter-individual coordination and pair-bonding. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 39, 54-60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2021.03.005

[14] Masonjones, H. D., & Lewis, S. M. (1996). Courtship Behavior in the Dwarf Seahorse, Hippocampus zosterae. Copeia, 1996(3), 634–640. https://doi.org/10.2307/1447527

[15] Faust, K. M., & Goldstein, M. H. (2021). The role of personality traits in pair bond formation: pairing is influenced by the trait of exploration. Behaviour, 158(6), 447–478. https://doi.org/10.1163/1568539x-bja10076

[16] Ainley, D. G. (1974). The comfort behaviour of Adélie and other penguins. Behaviour, 50(1–2), 16–51. https://doi.org/10.1163/156853974X00328

[17] Young, L. J., & Wang, Z. (2004). The neurobiology of pair bonding. Nature Neuroscience, 7(10), 1048–1054. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn1327

[Edited by: Isabel Kier]