You may be familiar with the axolotl (“ACK-suh-LAH-tuhl”, scientific name: Ambystoma mexicanum) – not only has the little guy been featured in popular games such as Minecraft, Fortnite, and Roblox, the internet has also grown very fond of its permanent Mona Lisa smile [8,5,19]. Beyond overwhelming cuteness levels and favorable recognition in the media, however, the axolotl also has great cultural and scientific significance.

Before this amphibian was a pixelated cave dweller, it was the subject of Aztec legend. The Aztecs believed that the axolotl is actually Xolotl, their god of fire and lightning, who disguised himself in this form to avoid being sacrificed [9]. Accordingly, “axolotl” is thought to roughly translate to “water monster” or “water dog” in Nahuatl, an ancient Aztec language [2, 24].

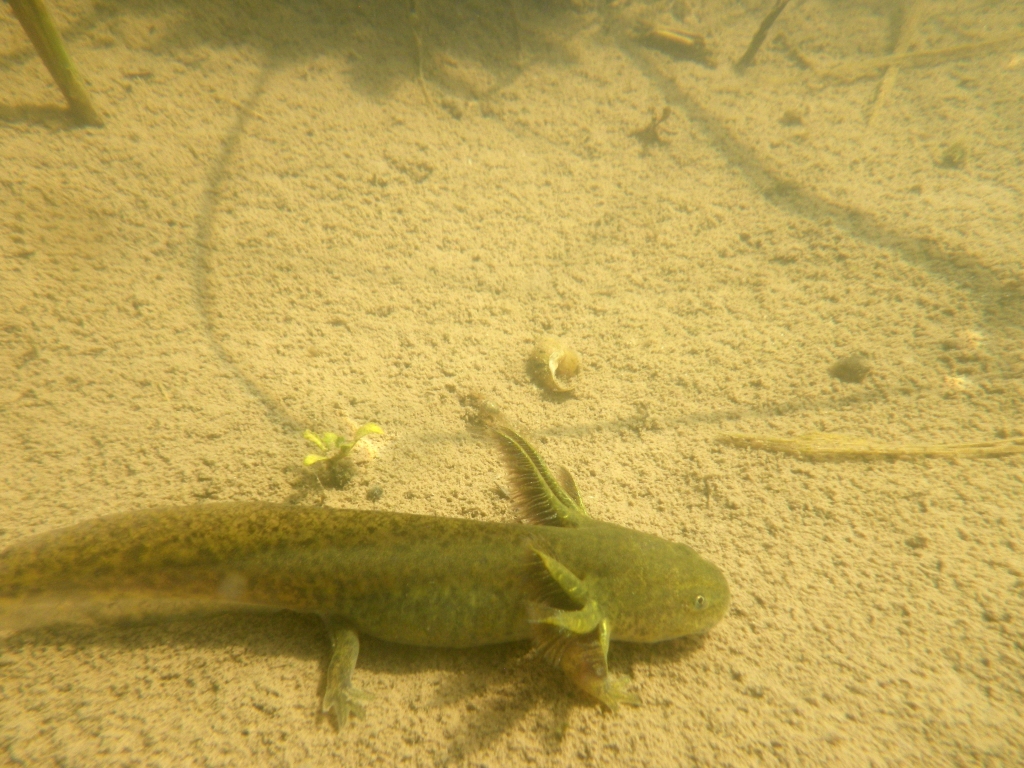

Unfortunately, these creatures are nearly extinct in the wild- while they once thrived in the high altitude lakes near Mexico City (previously named Tenochtitlan, founded by the Aztec people in the year 1325 [11]), they now inhabit only a few nearby canals due to pollution and desiccation (drying up) of their original habitat [7]. However, there are around one million axolotls in captivity, as these water monsters are commonly bred and used for science [34].

Regenerative Capability:

The main reason for the axolotl’s ubiquity in scientific research is its ability to regenerate various parts of its body throughout adulthood, such as its limbs, tail, heart, spinal cord, and even portions of its brain [33, 23, 9]. Sometimes, axolotls will even grow an extra limb during this process! Now they’re just showing off… Exactly why axolotls have this ability is unknown, but it seems to be an evolutionary adaptation in response to consistent selective pressures- essentially, axolotls probably developed this ability to avoid predators [31].

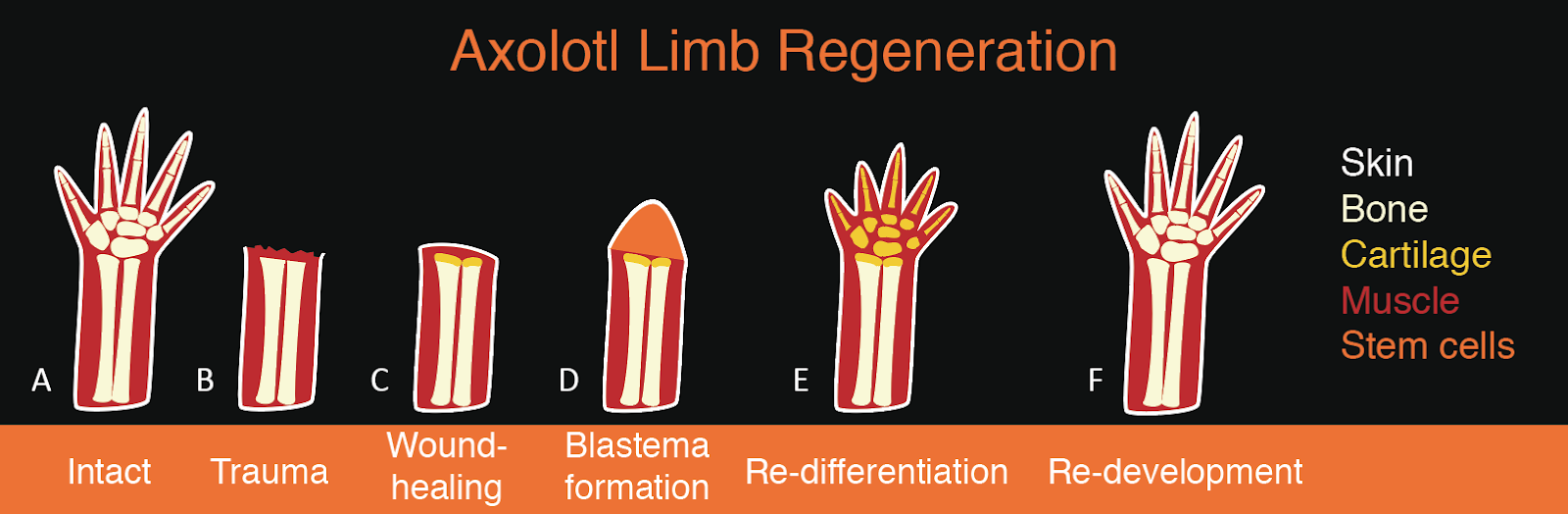

But how do these little rock stars actually grow back their lost limbs? When a part of an axolotl’s limb is amputated, a cascade of events is initiated. After initial blood clotting to stop the bleeding, cells from the healthy portion of the limb begin a process called dedifferentiation, which is a fancy way of saying that cells that were specialized to have certain identities go back to a more neutral state. This works similarly to human stem cells, which are able to become a wide variety of cell types. We humans have a lot of stem cells early in development, but as adults we have much fewer with a very limited capacity to form new cells from them [25]. Maybe if scientists can determine exactly how axolotls are able to dedifferentiate their cells, we can eventually trigger a similar process in humans, making human limb regeneration a potential (very distant) reality!

An important part of this dedifferentiation process is the formation of a cone-shaped structure called a blastema, which is a collection of these stem cell-like dedifferentiated cells at the site of the trauma. From there, the cells can re-differentiate to form the necessary cells to grow back the missing portion of the limb, such as skin, bone, and muscle cells. [16, 21]

Researchers previously thought that axolotls had an unlimited capacity to regrow limbs, but that no longer appears to be true. A 2017 study found that more than half of the axolotl limbs tested failed to significantly regenerate after 5 successive rounds of amputation [14]. Pushing the limits of the axolotl regenerative capacity is important, as it may help pinpoint why mammals struggle to regenerate in the same way.

Neoteny:

The axolotl’s superior regeneration ability may work in part due to its neoteny. Scientists use this term to mean reaching sexual maturity without going through metamorphosis- or in the words of Rod Stewart, being “forever young” [4].

Axolotls are a type of amphibian- but unlike most other amphibians that are born in the water and lose their gills during the transition to land, axolotls have evolved to spend their entire lives in the water and retain their gills throughout their lives (their cute external feathery appendages) [1]. Having gills allows them to stay underwater to avoid their (few) natural predators including storks, herons, and large fish while they use suction to feed on aquatic organisms like worms, small fish, and insects [35, 10]. When the water temperatures become temperate in the spring, axolotl mating season begins, where male and female axolotls engage in a waltz that culminates in the fertilization of hundreds of eggs [32]. These behaviors are made possible due to axolotls never losing their gills. One theory is that this happens because of the permanence of their native lakes, which never dry up, unlike other bodies of water that amphibians may be born into [9, 20].

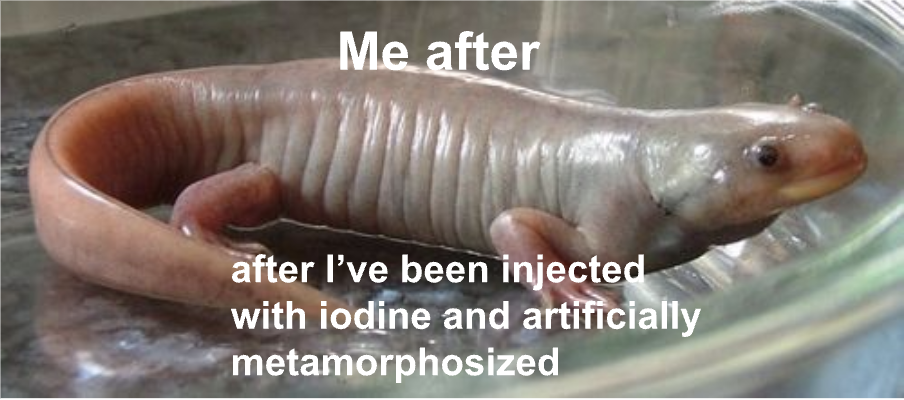

The axolotl’s close amphibian relatives produce a hormone called thyroid-stimulating hormone, which is required to start metamorphosis (i.e., losing the gills and moving to land). Axolotls don’t produce much of this hormone, though they do retain the ability to respond to it. If scientists experimentally inject an axolotl with thyroid-stimulating hormone they are able to artificially induce metamorphosis, after which axolotls can successfully live on land! This can also be done by injecting iodine, which axolotls can use to produce thyroid-stimulating hormone. When axolotls metamorphosize as a result, their bodies undergo various changes to help them live on land, such as the loss of gills and other swimming-related structures, the formation of eyelids, and the development of greater muscle tone [27, 30].

What We Can Do To Help:

Our favorite, incredible little water dogs are sadly in danger of going extinct. But all hope is not lost! In Xochimilco, the Mexican wetlands where wild axolotls currently reside, campaign groups are organizing various initiatives to prevent these guys from going extinct in the wild.

As the main threat to axolotl habitat is urbanization, groups such as MOJA (Movimiento de Jóvenes por el Agua, A.C.) are providing education to locals about how to live and work sustainably in this region in order to preserve the local ecosystem [15]. They are also using funding from donors worldwide to plant native tree species in the area, get rid of invasive species, and reduce pollution of the water canals. If you’d like to see the forever young (and forever cute) axolotls stick around for a while you can consider donating to MOJA or similar organizations working to restore their natural habitat [9, 22, 15].

One thing is for sure- the longer that axolotls stick around, the more memes like these we will get the pleasure of viewing. Thanks alotl for reading!

Written by: Erica Varga is a third year neuroscience PhD student at UC Davis studying the reason why uncertainty makes us anxious. While they’re not coding or designing experiments Erica likes rock climbing, playing Dungeons & Dragons and creating art. You’ll be able to see their art in various local art shows throughout the year.

References:

- “All about Amphibians.” Burke Museum, UW College of Arts & Sciences, http://www.burkemuseum.org/collections-and-research/biology/herpetology/all-about-amphibians/all-about-amphibians. Accessed 8 June 2024.

- AMNH. “Fast Facts: Axolotl.” American Museum of Natural History, American Museum of Natural History, 27 Mar. 2015, www.amnh.org/explore/news-blogs/on-exhibit-posts/fast-facts-axolotl.

- “Animal Welfarists.” Tumblr, animalwelfarists.tumblr.com/post/74889257584/i-just-watched-an-episode-of-qi-and-they-said-if. Accessed 9 June 2024.

- Arntsen, Emily. “Meet the Axolotl: A Cannibalistic Salamander That Regenerates Its Limbs and Might Help Us Better Understand Human Stem Cell Therapy.” Northeastern Global News, Northeastern University, 21 Oct. 2019, news.northeastern.edu/2019/10/21/northeastern-biology-professor-studies-axolotl-regeneration-to-further-understand-human-stem-cell-therapy/#:~:text=The%20axolotl%27s%20ability%20to%20fully,This%20condition%20is%20called%20neoteny.

- “Axo.” Fortnite Wiki, Fandom, Inc., fortnite.fandom.com/wiki/Axo. Accessed 8 June 2024.

- “Axolotl Care Guide.” Live Aquaria: Quality Aquatic Life Direct To Your Door, LiveAquaria, http://www.liveaquaria.com/article/450/?aid=450. Accessed 8 June 2024.

- “Axolotl.” Earth Day, 22 Apr. 2020, www.earthday.org/axolotl/#:~:text=The%20Axolotl%20or%20%27Mexican%20Walking,Lake%20Xochimilco%20and%20it%27s%20wetlands.

- “Axolotl.” Minecraft Wiki, Fandom, Inc., minecraft.fandom.com/wiki/Axolotl. Accessed 8 June 2024.

- “Axolotl.” National Geographic: Animals, National Geographic, http://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/amphibians/facts/axolotl#:~:text=But%20these%20Mexican%20amphibians%20are,%E2%80%9Cyoung%E2%80%9D%20throughout%20their%20lives.&text=Unlike%20other%20salamanders%20that%20undergo,stage%2C%20a%20phenomenon%20called%20neoteny. Accessed 8 June 2024.

- “Axolotl.” San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance Animals and Plants, San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, animals.sandiegozoo.org/animals/axolotl#:~:text=The%20axolotl%20has%20few%20predators,lakes%20and%20ponds%20they%20inhabit. Accessed 18 June 2024.

- “The Aztec Empire.” The Guggenheim Museums and Foundation, The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 2004, www.guggenheim.org/publication/the-aztec-empire.

- B, Epi. “Salamanders: Axolotl Questions.” Epiphany, 1 May 2020, epibee.wordpress.com/tag/salamanders/.

- Boardman, Madeline. “The Evolution of Rod Stewart.” Entertainment Weekly, Dotdash Merideth, 10 Jan. 2017, ew.com/music/rod-stewart-photos/.

- Bryant, Donald M., et al. “Identification of regenerative roadblocks via repeat deployment of limb regeneration in Axolotls.” NPJ Regenerative Medicine, vol. 2, no. 1, 6 Nov. 2017, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41536-017-0034-z.

- “Create a Refugee for the Axolotl and Save the Xochimilco Wetland.” MOJA , MOJA México & Colombia , http://www.moja.ong/donate/?gclid=Cj0KCQiAtJeNBhCVARIsANJUJ2ElWXhtyyyYzlGcSHXJUJoE7_qfCn5rpYNYx9NnLx0dE95kp19R_CYaArNpEALw_wcB. Accessed 8 June 2024.

- Dunlap, Garrett. “Regeneration: What the Axolotl Can Teach Us about Regrowing Human Limbs.” Harvard: Science in the News, 12 Jan. 2018, sitn.hms.harvard.edu/flash/2018/regeneration-axolotl-can-teach-us-regrowing-human-limbs/.

- East Bay Vivarium. “Axeolotl Meme.” Facebook, 20 June 2022, www.facebook.com/EBViv/photos/a.10151669115323697/10158881288773697/?type=3&paipv=0&eav=Afab7zCDzE7-uh0fWQ9_Vll8JwcRvY6_V5fPJBjABhTGUEiAZqHr-5O5Gb93SvKzH3Q&_rdr.

- Erdei, Kitti. “Barred Tiger Salamander (Ambystoma Mavortium Mavortium) .” Pinterest, 14 May 2018, www.pinterest.com/pin/32088216080894663/.

- “Find the Animals *how to Get Axolotl* Roblox.” YouTube, YouTube, 28 Dec. 2022, www.youtube.com/watch?v=jS2Yp6advkY.

- Friar, Greta. “Unusual Labmates: Nature’s Peter Pans.” Whitehead Institute, Whitehead Institute, 3 Apr. 2024, wi.mit.edu/unusual-labmates-nature-s-peter-pans.

- Gerber, Tobias, et al. “Single-cell analysis uncovers convergence of cell identities during axolotl limb regeneration.” Science, vol. 362, no. 6413, 27 Sept. 2018, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaq0681.

- Howard, Brian Clark. “Watch How Bizarre ‘water Monsters’ Get a Second Chance.” National Geographic, National Geographic Society, 11 Oct. 2016, www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/endangered-axolotls-conservation-mexico-city-chinampa.

- Le Bras, Alexandra. “New insights into axolotl brain regeneration.” Lab Animal, vol. 51, no. 10, 23 Sept. 2022, pp. 250–250, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41684-022-01063-3.

- OConnell, Rebecca. “11 Fascinating Axolotl Facts.” Mental Floss, Minute Media, 30 Mar. 2023, www.mentalfloss.com/article/63130/11-awesome-axolotl-facts.

- Pennock, Rebecca, et al. “Human cell dedifferentiation in mesenchymal condensates through controlled autophagy.” Scientific Reports, vol. 5, no. 1, 20 Aug. 2015, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep13113.

- PlumpScales. “Really Wanting an Axolotl to Smile at Me Rn!” Twitter, Twitter, 3 June 2020, twitter.com/PlumpScales/status/1268018576125915136.

- Proorocu, Marian, and Valentin I. Petrescu-Mag. “Axolotls and Neoteny: Those Who Forgot to Grow Up.” EBSCO, 2022.

- “R/Axolotls on Reddit: Meet My Five-Legged Axolotl Ponyo!” Reddit, 2019, www.reddit.com/r/axolotls/comments/c2y0e7/meet_my_fivelegged_axolotl_ponyo/.

- “R/Memes – Regeneration Gang Rise Up.” Reddit: R/Memes, 2019, www.reddit.com/r/memes/comments/ec94l2/regeneration_gang_rise_up/.

- Safi, Rachid, et al. “The axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum), a neotenic amphibian, expresses functional thyroid hormone receptors.” Endocrinology, vol. 145, no. 2, 1 Feb. 2004, pp. 760–772, https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2003-0913.

- Slack, Jonathan MW. “Animal regeneration: Ancestral character or evolutionary novelty?” EMBO Reports, vol. 18, no. 9, 26 July 2017, pp. 1497–1508, https://doi.org/10.15252/embr.201643795.

- Tanza, Laurance. “Axolotl Mating Dance.” YouTube, YouTube, 15 Jan. 2016, www.youtube.com/watch?v=jZVaTL-vYas.

- Vieira, Warren A., et al. “Advancements to the axolotl model for regeneration and aging.” Gerontology, vol. 66, no. 3, 28 Nov. 2019, pp. 212–222, https://doi.org/10.1159/000504294.

- Wee, Tori. “The Rise and Fall of the Amphibian, the Axolotl.” The Science Survey, 6 June 2023, thesciencesurvey.com/editorial/2023/06/06/the-rise-and-fall-of-the-amphibian-the-axolotl/.

- “What Do Axolotls Eat?” Sal-Site, Ambystoma.uky.edu, ambystoma.uky.edu/19-fun-facts-cat/67-what-do-axolotls-eat. Accessed 18 June 2024.

[Edited by Jacob Johnson and Alice Michel]