Over the expansive sawgrass prairies of the Everglades, a distant bright pink spot soars across the deep blue sky. Unfamiliar tourists may excitedly proclaim that they’ve spotted a flamingo. While American flamingos can be found in Florida, they are much less abundant and widespread than another big pink bird: the roseate spoonbill (Platalea ajaja).

Roseate spoonbills are named for their pink color and spatulate-shaped bills. Their unique appearance makes them one of the most peculiar-looking birds on the planet. Spoonbills (Genus Platalea, after the Greek word for “broad”) are wading birds closely related to ibises, herons, and egrets. Of the six spoonbill species, roseate spoonbills are the only one whose plumage is not primarily white and the only species native to the western hemisphere. Roseate spoonbills are distributed along the warm coastlines of Central America, the Caribbean, and northern South America, as well as vast interior wetlands, such as the Pantanal in Brazil. Roseate spoonbills are common in the southeastern US, inhabiting and breeding along much of the Gulf of Mexico and up the Atlantic Coast as far north as South Carolina. Some spoonbills are year-round residents near their breeding grounds, while others make short migrations from breeding grounds, often associated with seasonal changes in water levels and food availability. Sightings are rare in the western US. However, the occasional solitary bird makes its way to California, spotted as far north as Monterey (back in the 1970s).

As medium-sized wading birds, roseate spoonbills rely heavily on coastal and wetlands ecosystems for food. They prey upon minnows, crustaceans, and aquatic insects. Despite their primarily carnivorous habits, they also consume fruits, stems, roots, and other plant matter [1]. Their pink coloration actually comes from the pink-tinged animals and algae that they eat, much like flamingos [2]. Their bill morphology enables roseate spoonbills to efficiently forage by incorporating some distinctive behaviors. To capture prey, they move their ajar bill back and forth in the water, agitating the bottom and any associated small creatures. When spoonbills feel their bill contact a prey item, they rapidly snap it shut and lift it into the air, expelling water and devouring their meal before it has any chance of escape.

Like some other wading birds with elegant feathers, roseate spoonbills fell victim to the plume trade in the nineteenth to early twentieth centuries. Plume hunters heavily targeted them, nearly driving the US population to extinction. Florida Bay, the shallow estuary between mainland Florida and the Florida Keys, was one of their last strongholds. Yet in 1939, even Florida Bay was down to fewer than 30 nesting pairs [3]. In response, the Audubon Society established the Everglades Science Center and hired conservationist Robert Porter Allen to study and protect spoonbills. Naturalists at the time typically captured and killed specimens for study, but Allen set up a tent and a desk on a remote Key in Florida Bay amongst the nesting spoonbills. He sought a way to preserve the spoonbills by better understanding their ecology and behavior. The Everglades Science Center has been conducting annual roseate spoonbill nesting surveys in Florida Bay ever since. Largely due to Allen’s efforts and advocacy for the spoonbills, they rebounded locally and nationally, with approximately 1400 nesting pairs in Florida Bay by 1979 [3].

I spent my first job out of college as a seasonal field biologist with the Everglades Science Center, assisting with 2022 nesting surveys. Fieldwork in Florida Bay was tough. We boated around the treacherous sandbank-filled bay each day to different keys to search for nests by foot. Walking around Florida Bay’s keys involves either slogging through waist-deep mud or squeezing through dense tangles of mangroves, often accompanied by swarms of mosquitoes. Despite the less glamorous nature of the work, routine encounters with Florida Bay’s special wildlife, like crocodiles, sawfish, manatees, and endemic great white herons, made the job undoubtedly worthwhile. The highlight of the season was certainly when conservation photographer Mac Stone joined us in the field and captured an image of a banded parent spoonbill. In referencing the band ID it was found that the bird was at least 18 years and 3 months—making it the oldest wild roseate spoonbill ever recorded!

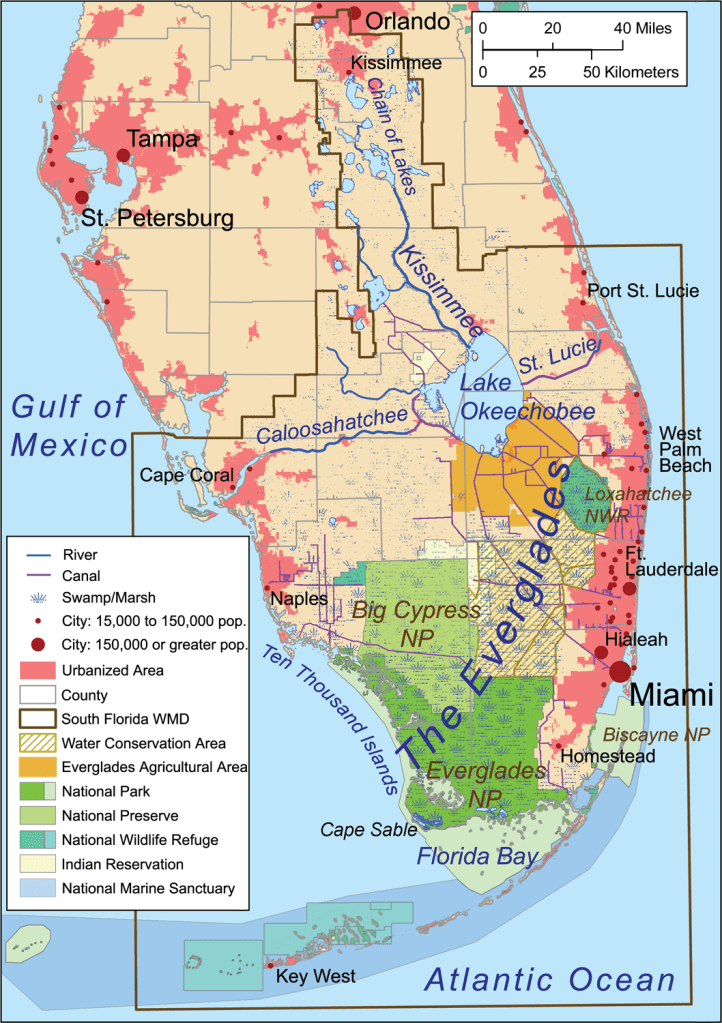

The Greater Everglades Ecosystem is a massive subtropical wetland stretching from the Kissimmee Basin just south of Orlando all the way to Florida Bay. It encompasses Everglades National Park, Big Cypress National Preserve, and dozens of other protected areas, hosting some of the greatest biodiversity in the US including over 120 endangered and threatened species [4]. Changes in natural hydrology associated with the development of South Florida have had a tremendous impact on the “River of Grass.” The Greater Everglades’ size has decreased by 50% and its freshwater flow by 70% [5]. The degradation of the natural hydrological cycle, combined with several other threats to the mosaic of ecosystems that form the Everglades, is the reason it is the only UNESCO World Heritage Site in the country listed as “In Danger” [6].

Roseate spoonbills have been called an “indicator species” for water quantity and quality in the Everglades [7,8]. This is because they are sensitive to changes in water level and water quality due to their feeding ecology. They require a myriad of prey items within their ideal foraging depth range, particularly during nesting season when they must feed themselves and their hungry, growing offspring. Often breeding in large colonies adjacent to foraging areas, sufficient, reliable prey must be available to support the whole colony for months as nestlings develop. Spoonbill nesting location, nest numbers, and nest production in relation to prey fish availability directly indicate hydrologic conditions, particularly water depth and salinity [8,9]. Roseate spoonbill nesting attempts and production have steadily declined in Florida Bay since the mid-1980s, likely due to inadequate water management infrastructure implemented around the time [8,10]. Meanwhile, their breeding distribution has simultaneously expanded throughout South Florida, likely to areas with more suitable water levels [11].

The beautiful, bizarre roseate spoonbill has faced many anthropogenic challenges for well over a century. Though they’ve rebounded from the plume trade, ongoing threats related to habitat degradation continue to afflict their population. Spoonbill distribution patterns and nesting trends will continue to be important for monitoring the health of the habitats that they and other wildlife rely on into the future. As substantial restoration efforts are underway, immense projects seek to re-establish historical freshwater flow regimes through the Everglades into Florida Bay. If we can reinstate natural flow, thousands of roseate spoonbills may once again return to nest.

Peter Aronson is a Junior Specialist in the Fangue Fish Conservation Physiology Lab. He assists with experimental studies on the behaviors, preferences, and environmental tolerances of native fishes, particularly salmon, sturgeon, and smelt. In his free time, he enjoys exploring the outdoors and nature photography. All photos here are his own, and you can see more of Peter’s work on Instagram @peteraronsonphotography.

References:

[1] Matheu, E. (1992). Family Threskiornithidae (Ibises and Spoonbills). Handbook of the Birds of the World, 1, 472-507.

[2] Fox, D. L. (1962). Carotenoids of the roseate spoonbill. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology, 6(4), 305-310.

[3] Powell, G. V., Bjork, R. D., Ogden, J. C., Paul, R. T., Powell, A. H., & Robertson Jr, W. B. (1989). Population trends in some Florida Bay wading birds. The Wilson Bulletin, 436-457.

[4] Stainback, G. A., Lai, J. H., Pienaar, E. F., Adam, D. C., Wiederholt, R., & Vorseth, C. (2020). Public preferences for ecological indicators used in Everglades restoration. Plos one, 15(6), e0234051.

[5] Perry, W. (2004). Elements of South Florida’s comprehensive Everglades restoration plan. Ecotoxicology, 13(3), 185-193.

[6] Finkl, C. W., & Makowski, C. (2017). The Florida Everglades: An overview of alteration and restoration. Coastal wetlands: alteration and remediation, 3-45.

[7] Lorenz, J. J. (2000). Impacts of water management on Roseate Spoonbills and their piscine prey in the coastal wetlands of Florida Bay. Coral Gables, Fla., University of Miami (Doctoral dissertation, Ph. D. dissertation).

[8] Lorenz, J.J., Langan-Mulrooney, B., Frezza, P. E., Harvey, R.G. and Mazzotti, F.J. (2009). Roseate spoonbill reproduction as an indicator for restoration of the Everglades and the Everglades estuaries. Ecological Indicators 9S: 96–107.

[9] Lorenz, J. J., & Serafy, J. E. (2006). Subtropical wetland fish assemblages and changing salinity regimes: Implications for Everglades restoration. Hydrobiologia, 569, 401-422.

[10] Lorenz, J. J. (2014). The relationship between water level, prey availability, and reproductive success in Roseate Spoonbills foraging in a seasonally-flooded wetland while nesting in Florida Bay. Wetlands, 34(Suppl 1), 201-211.

[11] Wolfe, E. P., Lefevre, K. L., & Lang, K. (2020). Expansion of roseate spoonbilll breeding distribution in Southwest Florida. Florida Field Naturalist, 48(1), 19-24.

[Edited by Alice Michel]

Great information, especially the details from the early studies. I would love to read a few of the early journals kept. Their numbers have greatly increased and now even breed in (hidden) places along South Carolinas ACE Basin.

LikeLike